Legacy Stories

Mike Pyle

Mike Pyle was a talented high school athlete at New Trier High School in Illinois. He went on to play football collegiately for Yale University and professionally for nine years for the Chicago Bears from 1961-1969. After he retired, Pyle became a broadcaster for the Bears on local radio in Chicago. In the 1990’s, Pyle’s behavior and attitude began to change. He suffered from mood swings and irrational anger and Pyle began distancing himself from social situations. Pyle passed away in 2015 at the age of 76 from a brain hemorrhage. After his death, he was diagnosed with stage 4 (of 4) Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy(CTE) as well as advanced Alzheimer’s Disease by researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank.

By Jim Proebstle with Samantha Pyle Buono and Candy Pyle

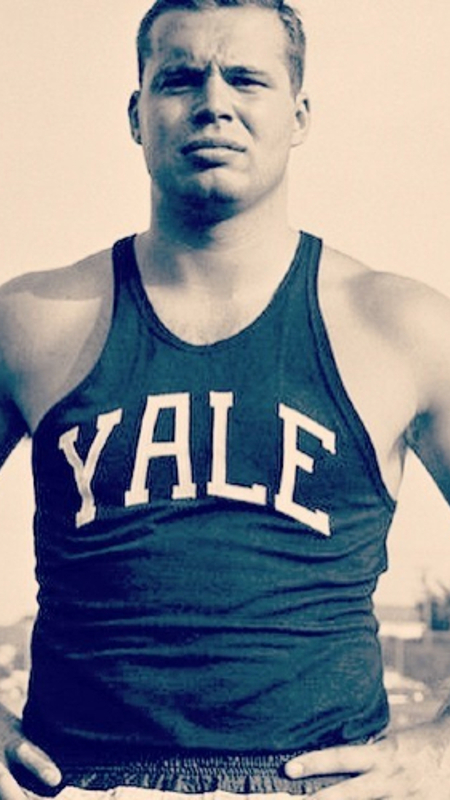

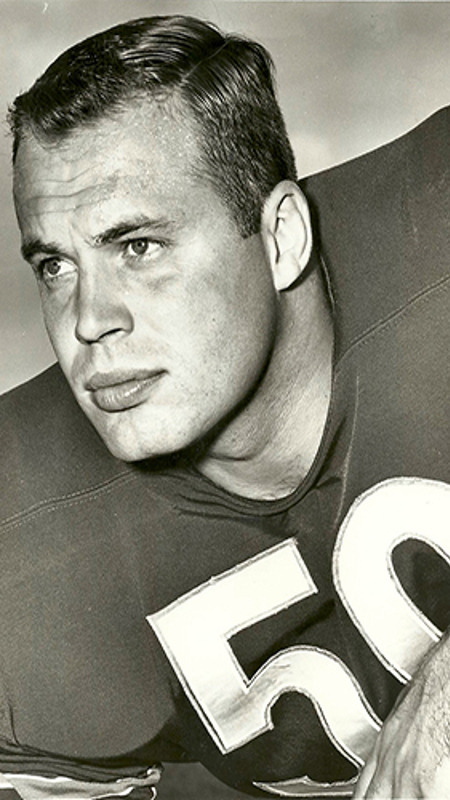

Mike Pyle attended New Trier High School in Winnetka, Illinois, where he was a multi-sport athlete with several state championships to his credit. He graduated in 1957 from New Trier and went on to Yale University, where he was a member of Skull and Bones. He was an offensive linemen for the Bulldogs and captained the undefeated, co-Lambert Trophy winner 1960 team. The 1960 team was ranked 14th in the final AP college football poll and 18th in the final UPI college football poll. Mike played nine seasons for George Halas with the Chicago Bears from 1961 through 1969. In 1963 he was named a Pro Bowler and served as the Bears offensive team captain from 1963 through his retirement. He was named to the Sporting News First Team - All Conference and the UPI Second Team - All NFL in 1963 and to the New York Daily News All NFL team in 1965.

Chicago's own

Mike’s return to Chicago to play for the Bears was special—it was home. He brought with him from Yale a unique ability to lead and, in this case, the Bears possessed a very talented group of performance driven athletes who would respond. He simply valued each player for their ability to contribute. It may also have been his sense of humor that complemented his effective leadership style as captain of the Bears for so many years, as the team chemistry and locker room comradery became a trademark of their success. Regardless, whether it was on the field or through his successful involvement in the many fundraiser and charity events filling his post-playing years, leadership and generosity of his own time was at the heart of Mike’s success. His life was always about “doing for others.” He is remembered as a good and loyal friend.

In 1969, Mike became a broadcaster for WGN radio, where he was the Bears pre and post-game program host, as well as the host of a Sunday sports talk show. He later co-hosted the "Mike Ditka Show" when Ditka coached the Bears. In 1974 he served as color commentator on the broadcasts of the WFL's Chicago Fire on WJJD. This celebrity status fueled the countless requests to be in the public eye. In some respects it provided Mike a way to stay in the game even though his playing days were over, not an uncommon reaction on the part of many athletes who have reached the rarified air of becoming a household name.

Undefined change became the norm

In the early ‘90s Mike’s behavior problems became an issue. No one knew about CTE and its related demonstrations of rage and temper outbursts. Bad behavior shifted from logical reactions of disagreement when he was young to absurd, over-the-top reactions when he was older. OCD and micromanaging in a mean-spirited and judgmental manner became the norm. He went from being a people person who was the last to leave a party to a deep stage of withdrawal, not talking other than to answer questions, and when he did talk he yelled, always finding fault with what was wrong. It never occurred to the family that Mike was suffering from a disease –they just didn’t know—nobody knew. An excessive consumption of alcohol, a common form of self-medication, contributed to a skyrocketing display of difficult, antisocial behavior.

Mike’s true friends from years as an athlete and public event promotions were forgiving and tremendously loyal in his decline. His choice of jobs and job prospects, however, predictably declined rapidly, as the behavior changes became uncontrolled. It’s important to remember that NFL players did not make a lot of money in the ‘60s. The 2007-2008 hip replacement represented a low as the rehab forced an unforeseen alcohol withdrawal and drying out period involving hallucinations, physical threats and needed security support. After his recovery, Mike carried on in limited public engagements because of his enduring celebrity status. People would enable him to stay involved as long as the endorsements held out. Not surprisingly, the conflict from the growing CTE behaviors brought an end to the public role. Sadly, Mike’s ability to “do for others” disappeared. Organizations such as Better Boys Foundation, Juvenile Diabetes, and the Jack Quinlan Charity Golf Tournaments, to name a few, lost an effective and avid celebrity promoter. In time, Mike was blocked, pushed aside and marginalized as a past president of the NFL Retired Players Association from the ‘60s. His psyche was devastated as he attempted to continue the good fight for the older players. The focus and politics were shifting to the newer players, however, and away from the physical and medical needs of the older players who built the NFL.

The homefront

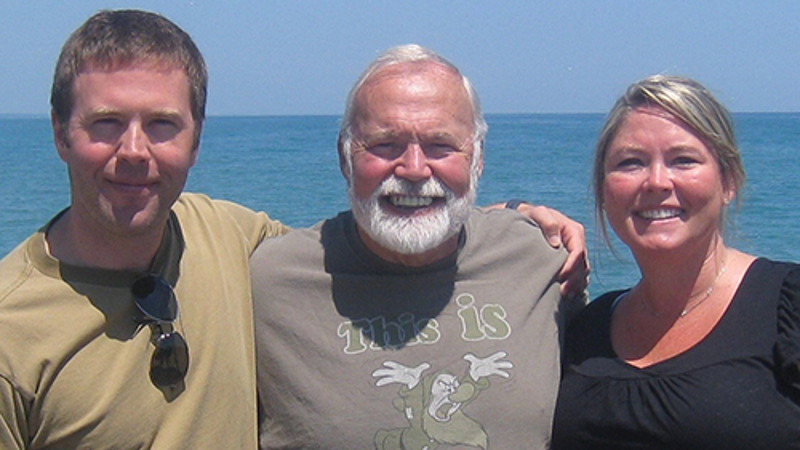

Candy, Mike’s second wife for over thirty years, kept the blended family with four children intact as Mike’s need to do for others occasionally worked to the detriment of the kids. He was always doing for others—a favor, a letter, a charitable engagement, etc. competed with his family duties. The priorities of “doing for others” always came first. In the end, he would never say no to a request—the player inside of him always wanted to be in the game—making a difference. Living with a retired professional athlete led to weekly individual, couple’s and family therapy sessions as they coped with the entitlement of the famous athlete that was losing his place in the sports headlines. Depression and dysfunctional family dynamic issues were addressed with anti-depressants in order to mitigate Mike’s rages. Through the process however, the family members ultimately recognized Mike was suffering from a serious illness. Mike was the love of Candy’s life and witnessing Mike’s decline was the hardest thing she’s ever had to endure. It was sad that the family didn’t know what was happening and that the disease had a name—chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

Despite the obstacles, Mike pushed forward choosing jobs in sales that didn’t always work out, and when customers wouldn’t buy his product his anger became obvious. Mike may have been taken advantage of because of his name recognition, as it appeared that he frequently was not the right person to sell many of the products he represented. This lack of success, coupled with unsound money decisions on his part, furthered family difficulties.

The 88 Plan

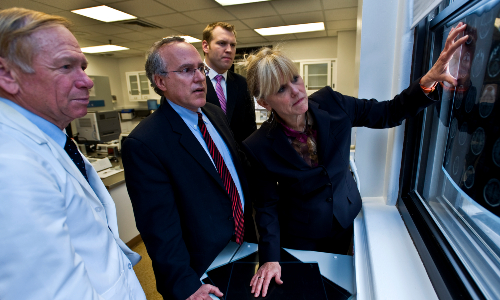

Around the years 2000-2001, Mike’s symptoms of dementia became apparent even though Mike acknowledged only two or three concussions in his career. His condition worsened as a result of the repetitive sub concussive blows to the head, common to a center’s position, and in 2013 his family was forced to put him into a full-time assisted living facility. Mike was accepted into the Silverado, a national chain of assisted living facilities and a preferred provider to the NFL.

The NFL had created The 88 Plan, a brain trauma program named for Hall of Fame tight end John Mackey, whose number was 88. Mackey was suffering from CTE dementia by the time he died in 2011. The 88 Plan’s goal was to treat all former players with at least three years of service that were suffering from dementia. The plan had very strict NFL guidelines and would only reimburse the families for the first $88K of expenses incurred. Since many of these players had little money they could only afford the Silverado because of The 88 Plan. Ironically, however, The Plan didn’t always cover all of the expenses, often leaving families in debt. Two hundred and twenty-three players have been approved thus far for The 88 Plan since its inception in 2005.

Mike Pyle suffered in a vegetative state at the Silverado and died on July 29, 2015 from a brain hemorrhage complicated by an additional diagnosis of Stage IV CTE dementia and advanced Alzheimer’s.

Football in the future

Two of Mike’s grandsons (12 and 14) play flag football and enjoy it. Both mom and grandma agree that the few new skills learned in tackle football at their age aren’t worth the risk considering the vulnerability to the developing 8-14 year-old brain. Samantha, the boys’ mom, has deferred any decision to support the boys’ involvement in tackle football until the game becomes safer. She does recognize that some boys have the need for rough and tumble contact, but ultimately, her boys’ safety is of primary concern. Samantha has been very involved with the great things being done by the Concussion Legacy Foundation. With her help, Team Up Speak Up Day was successfully launched in the Palm Desert schools. Candy, the boys’ grandmother, is not convinced that football, as we know it, is worth the risk. Both agree, however, that if either of the boys play tackle football it will be in a world very different from their grandfather’s

In summary

When you consider the body of Mike’s work throughout life, whether in football, the public eye of non-profit organizations or with his family, his purpose was always true—adding value with his devotion and passion. He was a wonderful man and it was a terrible waste to lose him. Even with the many benefits that come with celebrity status, it’s unfair that so many players in a similar position to Mike’s are paying the price for ignorance regarding the devastating impact of concussions. A very close friend of Mike’s, as well as of the family, would agree that losing such a good friend and beautiful person was an empty outcome considering the commitment he gave.

You May Also Like

Living with suspected CTE can be difficult, but CTE is not a death sentence and it is important to maintain hope. Find out how.

Living with CTE

Although we cannot yet accurately diagnose CTE in living people, a specialist can help treat the symptoms presenting the most challenges.

CTE Treatments