Legacy Stories

Tommy Vaughn

Thomas Robert Vaughn started playing football at age seven and went on to become a high school All-American, a star at Iowa State University, and a Detroit Lion for seven years. He retired from football in 1979 at age 29 due to concussions. A few years later, Vaughn started experiencing anxiety, panic attacks, mood swings, aggression, and memory issues. He was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease before his death in 2020 at age 77. He was later diagnosed with Stage 3 (of 4) Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) by researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank. Vaughn’s daughter is sharing his store to reveal how CTE impacted their family and to encourage other families affected by CTE to stay empathetic, hopeful, and kind.

A historic career

Tommy Vaughn grew up in Troy, Ohio as the oldest of five children and shouldered the responsibility that many eldest siblings are dealt. Vaughn had to help care for his young siblings but still found time to play sports with neighborhood friends. He started playing tackle football in local parks when he was seven years old.

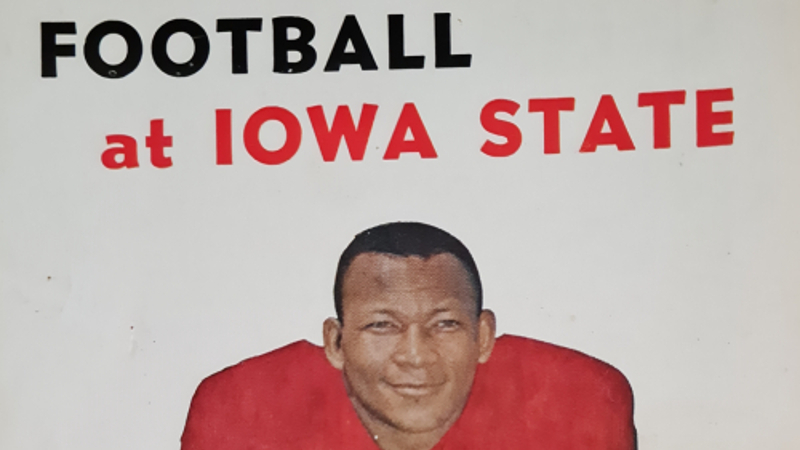

Along with football, Vaughn lettered in baseball and basketball at Troy High School. While he received scholarship offers for all three sports, he followed his love of football and accepted a scholarship to Iowa State University. There, he would become the Iowa State Athlete of the Year in 1963 and an Academic All-American in 1964.

For his athletic accomplishments, Vaughn would later be inducted into the respective Hall of Fames for The City of Troy, Iowa State University, and Troy High School.

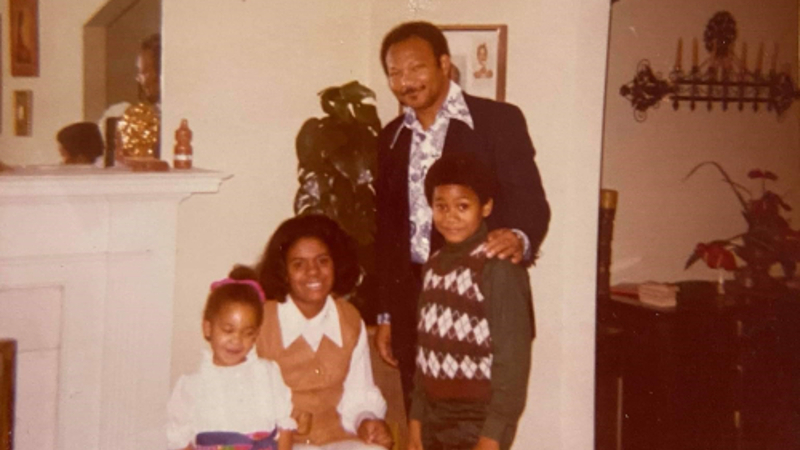

After his decorated college career ended, Vaughn was drafted by the Detroit Lions and married his college sweetheart, Cynthia, in 1965. They had two children, Terrace and Kristal.

Vaughn never missed a game in his seven-year career in the NFL. During those seven years, there were three times he woke up in a hospital room after being knocked out in a game. After the third knockout, a doctor warned him of the dangers of continuing to play if he suffered more concussions. In 1972, Vaughn chose his health and his family over football and retired at the age of 29.

Life after football

Growing up, Vaughn was raised to be humble. Despite being an NFL star, Kristal Vaughn says she never saw her dad think he was better than anyone else. He always made time to sign autographs for young fans and his bright personality followed him wherever he went.

When she speaks about her dad, she remembers him far less for his football accolades and much more for his kindness and intellect.

“He was an intelligent, happy, nerd,” said Kristal. “He was like Sheldon from The Big Bang Theory, but athletic.”

Vaughn enjoyed a robust life after football. He acted in the movie Paper Lion, earned his master’s degree, was a general manager at the Chrysler Corporation in Detroit, the President of Union National Bank of Chicago, and a high school teacher. Despite his success in business and education, Vaughn couldn’t stay away from the game for long.

“He loved teaching the game,” said Kristal. “My dad was the most giving, caring person in the world."

He became an assistant coach of the World Football League’s Detroit Wheels and then later for his alma mater at Iowa State University, the University of Wyoming, the University of Missouri, and Arizona State University.

Later, Kristal heard from many of Vaughn’s former players and students. Many of them told her about how coach or Mr. Vaughn never gave up on them.

Much to his dismay, Vaughn often worked long hours in coaching. After a long day, Vaughn often woke his children up to bake pies. The activity served two purposes: squeeze in precious family time and satisfy his legendary sweet tooth.

“I never got to know my real daddy”

For all the wonderful moments the Vaughns shared together, their household was not always a safe place.

Shortly after Vaughn retired from the NFL, his family noticed him become more anxious. Kristal remembers her father’s anxiety first manifesting into violent outbursts. She says her father always had a soft spot for animals, but he began taking his anger out on the family dog.

As Vaughn’s symptoms progressed, Kristal says his anxiety and agitation led to physical violence toward her mother and siblings.

When Vaughn moved the family from Detroit to take a coaching job at ISU, Kristal says her parents separated for six months because Vaughn didn’t resemble the man her mom Cynthia fell in love with.

The type of man Cynthia once knew was one their children would never get to meet.

“I never got to know my real daddy,” said Kristal. “And that’s not fair.”

When the family was in Iowa, Vaughn was prescribed medications to help manage his symptoms. Terrace caught on that his father was taking “puppy uppers” and “doggy downers” to regulate his emotions and behaviors. He told his sister to remind their father to take his pills if he was acting out. Tommy Vaughn was later diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

To cope and to protect herself, Kristal learned from a young age to remove herself from the situation whenever things at home became hostile. A self-described nerd herself, Kristal found refuge in books at her local library.

“I learned to not try to soften it,” said Kristal. “Don’t get involved with it, let them have their moment. Things will calm down.”

In 1985, Vaughn took a coaching job at Arizona State University. While in Arizona, Vaughn’s short-term memory began to decline. Kristal remembers her father would frequently repeat himself but would deny the repetition when anyone brought it to his attention.

Through her role as a social worker at a rehabilitation center that served brain injury patients, Cynthia gained a better understanding of how to work with her husband’s symptoms. She encouraged him to begin seeing a psychiatrist in Scottsdale who prescribed better medications to help stabilize Vaughn’s behavior.

Medications helped, but only to a point. Vaughn’s verbal filter disappeared over time, leading him to say vulgar or hurtful things to those around him, only to forget he said them minutes later. This pattern led his wife and children to follow the motto of, “if he didn’t remember, it didn’t happen and move on.”

As Vaughn aged, his mood swings and behavioral changes took a turn for the worse. In his late 60’s, he was the lieutenant governor of the Optimist Club youth program in Arizona. Every week, Optimist Club leadership met for breakfast at a local diner. One day, Vaughn misinterpreted a comment a waitress made and threatened her. Management asked Vaughn to leave and to never come back.

Vaughn suffered from panic attacks for much of his post-football life. At first, the episodes occurred every few months. By 2013, the attacks became weekly occurrences, usually triggered by trivial matters.

In 2015, Cynthia decided to bring Vaughn to the Barrow Institute in Phoenix, Arizona where he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

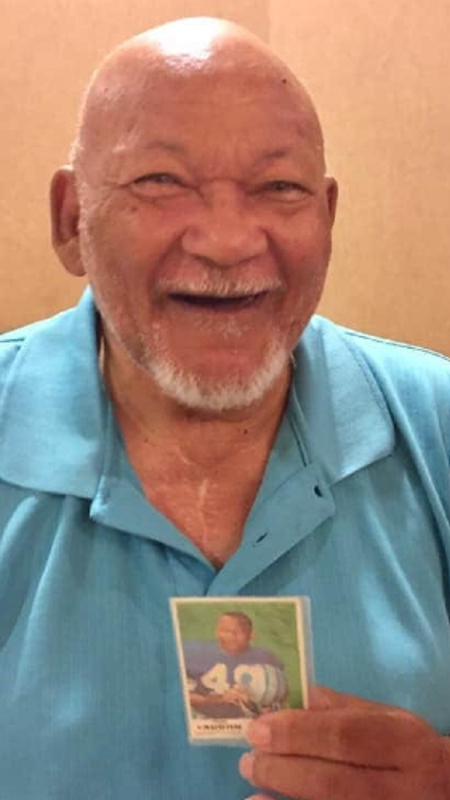

Vaughn had been on a progressive downslide for years, but his football career and extensive concussion history was never discussed as a culprit until he reached his early 70’s. Vaughn began to connect the dots between the repetitive head trauma he endured throughout his football career and the symptoms he struggled with for much of his life. He later told his family he wanted his brain to be donated to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank for CTE research.

As things worsened, Vaughn’s family desperately needed support to help manage his declining condition. That support came from an NFL contemporary of Vaughn’s.

“I have to be grateful for the 88 Plan,” said Kristal. “There is help out there. You’re not by yourself.”

The 88 Plan is named after Hall of Fame tight end and Legacy Donor John Mackey, who wore number 88 in the NFL and played in the league with Vaughn. Mackey died in 2011 after a long battle with what was eventually diagnosed as CTE. His public struggle with the disease led to the 88 Plan, which provides $88,000 a year for families of former players living with dementia.

Eight months after starting to receive 88 Plan benefits, Vaughn died at age 77. His family fulfilled his wish to have his brain studied, and Brain Bank researchers posthumously diagnosed him with Stage 3 (of 4) CTE.

“Do you guys get this?”

After she learned her father had CTE and not Alzheimer’s, Kristal was immediately taken back to a traumatic memory.

Kristal has a history with traumatic brain injury herself and suffers occasional seizures as a result. Once, in the last years of her father’s life, she was coming out of a seizure, laying down on the floor. She came to as her dad was pounding her head into the ground, screaming at her to wake up. In the chaos, Vaughn got frustrated at Cynthia and struck her as well.

“30 years ago, he would never have done that,” said Kristal. “He had the biggest, most beautiful heart.”

To other families with loved ones affected by possible CTE, Kristal wants to ensure they never abandon their loved one, but to also always prioritize their own safety. She says the lesson she learned as a child – to remove herself and to not engage with her father when he became aggressive – is vital to caregiving for someone with potential CTE. In her experience, her father would always calm down if given enough time.

She also urges those in power in the NFL to take player welfare more seriously and consider how a former player’s symptoms of CTE can devastate a family.

“I want to ask them, ‘Do you guys get this?’”

Despite the tremendous adversity she and her family have faced, Kristal retains an eternal sense of optimism. Her lasting message to other CTE families is one of resilience.

“We made it,” said Kristal. “We survived this. You can too.”

If you are being physically hurt by a family member or loved one, know it is not your fault and there is help available. For anonymous, confidential help, 24/7, please call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233 (SAFE).

Are you or someone you know struggling with symptoms of suspected CTE? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you. Click here to support the CLF HelpLine.

You May Also Like

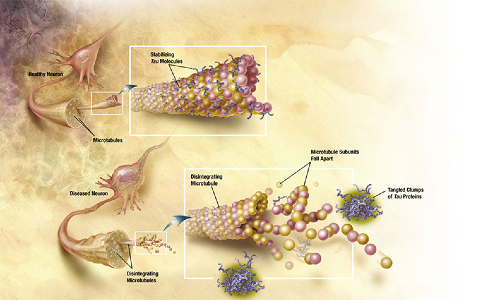

Learn about symptoms, risk factors, and what causes the neurodegenerative disease Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

What is CTE?

Living with suspected CTE can be difficult, but CTE is not a death sentence and it is important to maintain hope. Find out how.

Living with CTE