Legacy Stories

Tom Johnson

Tom Johnson was a standout young athlete in Brockton, Massachusetts. Johnson frequently got his “bell rung” as a star on the Brockton High School football team before continuing his football career at Colgate University in New York. He suffered two diagnosed concussions playing at Colgate before graduating in 1993. After a successful stint in the business sector, Johnson enlisted in the Marines. After being discharged in 2006, he struggled with PTSD, bipolar disorder, and alcoholism. He died on February 8, 2015 at age 44. His brain was later studied at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank, where researchers diagnosed him with Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

By Aini Johnson, Tom's mother

On the morning of February 8, 2015, I received the call from Tom’s wife. She told me Tom was gone. At first, I thought she meant he had left. I guess in a way he did. He left in the middle of the night and escaped the demons that haunted him during the latter years of his life.

Tom was the youngest of my three boys. He grew up in Brockton, Massachusetts, which is known as the “City of Champions” because boxing legends Rocky Marciano and Marvin Hagler grew up there. Tom’s father left our family without notice when Tom was only three years old. Despite growing up in a single parent home, there was no shortage of love from myself and his two protective older brothers, John and Dave. Tom and his brothers were gifted athletes at an early age and played baseball, football, basketball and several other sports. As a single mom working multiple jobs, I was thankful for athletics to keep them busy and largely out of mischief. I could never have envisioned Tom’s gift for all sports, particularly football, would contribute to such a marked demise in his quality of life and a premature death. It’s a parent’s worst nightmare, and I will always struggle with this guilt.

In addition to being a gifted athlete, Tom was an outstanding high school student, a member of the National Honor Society, and a very well-liked person. The combination of his athletic and scholastic talents made him stand out to his friends, teachers, teammates, and to his renowned high school football coach, Armond Colombo. Tom had strong beliefs about right and wrong, and he developed many lifelong friendships growing up in Brockton. Tom was an unconditional friend and his friends’ battles were Tom’s as well. His confidence and lack of pretense enabled him to converse with a homeless person just as easily as he could with President George H. W. Bush, who he met while attending the President’s Cup golf tournament.

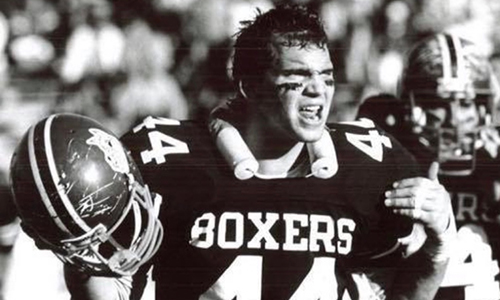

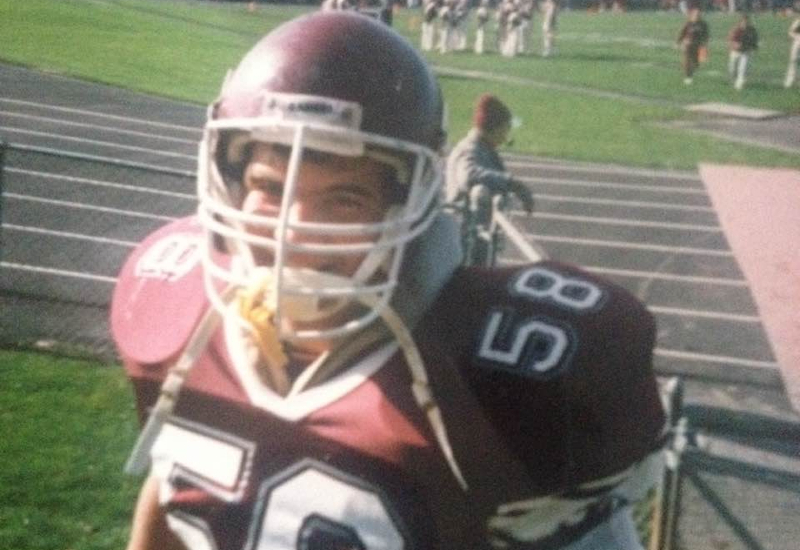

Tom played on the varsity football team as a freshman and was a star player each of his four years. This was a significant achievement considering the rich football history at Brockton High. The team went on to win three Massachusetts High School Super Bowl’s during the four years he played, losing only one time in his four seasons. Tom was co-captain and team MVP his senior year and named to the Enterprise All-Scholastic honors and selected to the Shriners All-Star team. Posthumously, Tom was inducted into the Brockton High School Hall of Fame in 2015.

Tom occasionally played fullback, but his primary position was middle linebacker. Tom loved battles, and at this position, he could outsmart, anticipate and use his speed and strength to tackle opposing ballcarriers. “It’s a gridiron war,” he and his teammates would often say. His teammates gave Tom the nickname “Captain Crunch” because he played with such reckless abandon to ensure his helmet connected with the ball carrier. Back then, Brockton players often compared helmets to measure who had collected the most dents and scratches throughout the season. The more damaged the helmet, the better. Tom’s helmet was frequently the most damaged.

During his high school football career, Tom suffered many “bell-ringers,” as they were called then. These were frequent, and not taken seriously by Tom, his teammates, or any of us. During one game against a team from New York, Tom suffered an especially serious concussion and was taken by ambulance to the hospital. Despite being diagnosed with a concussion on Saturday, he was back at football practice on Monday. During Tom’s high school years, 1985-1988, concussions weren’t newsworthy or ever a deterrent to sports.

Tom was offered several scholarships from various colleges and universities. He decided to attend Colgate University in Hamilton, New York. He played less in college than in high school, primarily due to a poor relationship with his coaching staff. In a game against Army his junior season, he suffered another serious concussion. He was not examined and diagnosed until several days after the impact and was sidelined for the next game. Soon after, people close to him noticed escalations in certain behaviors and we became concerned with his mental health.

Tom was always excitable and prone to fights, but after that concussion he became more erratic and he frequently escalated minor conflicts. He began drinking more often and acting out in ways that occasionally resulted in property damage and fights. At one point during his senior year, he was asked to take a leave of absence from school after an unprovoked altercation. Previous attempts by a girlfriend to get him to engage in therapy at school counseling sessions were short-lived. When Tom came home to be with his family for that year off from college, he told us about a traumatic incident that occurred during his childhood. After that admission, he willingly participated in therapy sessions and seemed to be on a great track as he returned to Colgate to complete his senior year and graduate in 1993.

After college, Tom moved to New York City and became an assistant specialist on the American Stock Exchange with the prominent firm Spear, Leads & Kellogg. He was considered such a prodigy at auction market trading that he was assigned to support one of the ASE’s busiest and most high-volume stocks: Motorola. After several years in New York, he realized how much he missed his family and friends and decided to move back to Massachusetts where he found work with Citigroup in their analyst program.

It was after a trip to Ground Zero to volunteer after the events of September 11, 2001 that Tom surprised everyone with his decision to enlist in the Marines. No one could have stopped him; he was incredibly determined to serve his country. In 2002, Tom departed for boot camp at Parris Island, NC before being deployed to Iraq. He served honorably on special operation tours and was awarded several commendations, including a Global War on Terrorism Service Medal, the National Defense Service Medal, and a Medal of Good Conduct.

Tom was discharged in 2006. Despite his commendations and awards, Tom was severely affected when he came back home. His behavior was erratic and irrational, his drinking was excessive, and his tendency to resort to violence escalated. He no longer resembled the incredibly loving son, brother, uncle, and friend we all knew. We were all concerned for him.

His condition grew worse with each passing year. In 2007, Tom attempted to take his own life. He was taken to a local hospital and then transferred to the Brockton VA Hospital for observation and treatment. He remained there for two weeks. He worked hard to convince his treating psychologist that he would be OK with outpatient therapy and he agreed to go to AA meetings. He seemed to be getting the help he needed and returned to spending time with friends and family. For these reasons, we saw the attempt to end his life as an aberration and not something we would ever revisit again.

Soon after, Tom received a job offer to work at the Naval Academy Prep School (NAPS) in Newport, RI. For a few years at NAPS, he was at his happiest professionally and seemed to be on the most positive trajectory. He worked as a system engineer and volunteered as an assistant football coach, mentoring kids who he truly loved. He also obtained a Master’s in Science Communication from Stayers University in Virginia. All seemed to be going great for Tom and I had never seen him happier.

The changes began to creep into our lives so slowly it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly when they began. Perhaps the first blow can be tied to when the chain of command at NAPS changed and Tom was informed his position and coaching role would be eliminated, along with his assistants. He was living away from home, so I did not see him enough to notice any day-to-day issues. Following an altercation at his brother’s home, he admitted himself to a drug and alcohol rehabilitation facility on Cape Cod. He maintained a position with NAPS, but they were now aware of his struggles and were initially very supportive to his illness.

Next, Tom bought a home in Middleboro and invited his fiancée and her son to live with him. They married shortly afterwards. Over the next two years he and his wife participated in AA programs, but would continuously relapse, rehab, and relapse again. He lost his job and his homelife was volatile and unstable. For a while, Tom was very open to receiving help. Around this time though, he became more rigid in what treatments he would participate in. He did try a long-term rehab program at the VA where he was diagnosed with PTSD. Doctors also considered a bipolar diagnosis and he was given medication. At that time, no one knew the true cause of his suffering.

A physical altercation then led to jailtime for Tom. After he was released, he seemed to lose all enthusiasm for life and his fighting spirit. An athlete who loved engaging in physical activities no longer cared about exercise or maintaining a healthy lifestyle, allowing his overall health to deteriorate. Most notably, he cut off communication with lifelong friends and family, essentially anyone who was trying to help him help himself. His lifetime of sociability and gregariousness contrasted with his devolution into reclusive behavior. His close relationships with his two older brothers whom he idolized became contentious, fraught with tense accusations, and even violent.

In December 2014, Tom called me crying to say he believed he was dying. We had the Middleboro police go to his home and escort him to the Bedford VA hospital. Tom called me after arriving to thank me for saving him, but he asked that I not visit since he had a lot of thinking to do. Sometimes that conversation haunts me. I questioned whether I should have overruled his request and gone to visit him. I was entirely unaware that he left the hospital and the program he was enrolled in until I received the call that he had died. Though I told him countless times during his difficult years, I never got the chance to tell him then how proud I was to be his Mom. I never got to remind him how I still loved him to the moon and back and always would.

During the final years of Tom’s life, he did his very best to tackle the mental pain and anguish he suffered like he had when he was a football player. He would often complain of excruciating headaches and say how he couldn’t rein in painful, rambling thoughts. We attributed the symptoms to Tom’s tendency to overthink or to his alcohol abuse. Even when he didn’t appear to be trying, Tom was fighting an internal battle with his entire being, a battle within that was unwinnable – mentally and physically. There were times when we thought he was getting better, but it wouldn’t last. None of the numerous hospitalizations or stays in rehab facilities to recover his life could bring Tom back to a place of calm or equilibrium. His life became what he described as an unrecognizable, living hell.

A few times when I went to his side and held him, he would ask me to please pray with him and his prayer was always the same, “Mom, please ask God to bring me home. I don’t want to live like this anymore.”

At the time Tom passed away, our family knew very little about CTE until his brother-in-law, Kevin Haley, notified us about the Concussion Legacy Foundation. He suggested we donate Tom’s brain to be studied for Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, or CTE. We decided to donate his brain, and about a year later, researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank diagnosed Tom with CTE.

I will always be extremely grateful to Kevin for providing this information and helping us complete the brain donation process. Learning about CTE has changed our lives and aided us in our grieving process. Gaining an understanding of what was happening within my son’s brain helped us understand those years where we could not comprehend his changes. We just wish we had known sooner, before it was too late to make a difference for Tom. The most important thing now is to continue the work and to expand the awareness for other families experiencing what we did and provide them with hope, and measures they can take for someone they love.

I want to extend my heartfelt thanks to Lisa McHale and Dr. Ann McKee and the entire research team for their painstaking diagnosis and patient explanation of the pathological findings. For me, my family and everyone else who loved Tom, the CTE diagnosis helped explain the devastating effects on Tom’s life and greatly assisted us in healing from his death.

Tom is missed every single day, but no longer are our memories fixated on the events of those traumatic final years because we’ve been blessed with an ability to understand what caused them. We now remember Tom as he was before he began to experience the symptoms of CTE. The son, brother, uncle, friend, and person he was is the memory that will forever live in our hearts.

If you or someone you know is struggling with probable CTE, or lingering concussion symptoms, ask for help through the CLF HelpLine. We support patients and families by providing personalized help to those struggling with the effects of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you.

You May Also Like

Vietnam veteran Allen Way suffered from PTSD and TBI symptoms before researchers diagnosed him with CTE after death. Learn about his struggle, and beautiful life of service in his Legacy Story as told by his widow.

Read Allen Way's Legacy Story

When he returned home from the war, Keith Pinkham struggled with the demons that afflict many soldiers. A devoted husband for 32 years, he died at just 65. Keith's wife donated his brain to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank.

Read Keith Pinkham's Legacy Story