Legacy Stories

Shelton Paradis

Sheldon Paradis was a talented football player at Boston College and then the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He went on to coach the football at Timberlane High School in New Hampshire. He was a father to four children and multiple grandchildren. Paradis battled constant mood swings, and irrational decision-making from early adulthood on. In his later years, he struggled more with his speech and was ultimately diagnosed with Alzheimer's Disease. After his death in 2008, his family donated his brain to the UNITE Brain Bank to honor Sheldon’s lifelong legacy of helping others. Researchers at the Brain Bank determined he had CTE. Sheldon’s family decided to raise awareness of CTE, show how the disease can affect patients and their families, and educate others on the risks of engaging in contact sports at younger ages.

“We ran through three divorces, seven children, many failed relationships, jobs, deaths of friends, and all our downfalls and victories, good times and bad. He was possibly the best man I have ever known.” – Bill Marro, Shank’s close friend

His Humor Persevered

By Eileen Devlin, Shank's wife

Shank’s initial symptoms were aphasia – difficulty in speaking and the added component of difficulty understanding spoken language. While you could always seeing him struggling to find the correct words, the ones he would finally speak were close to what he really wanted to say, but not quite on the mark. This made for some funny misspeaks and Shank always joined in the laughter. He loved to laugh. The following are some funny moments his family chooses to remember instead of the difficult times as he became sicker:

Shank was explaining the large mountain near us when we lived up in the greater North Conway, NH area and kept calling it Mouse Washington rather than Mount Washington. He did not even hear his mistakes!

“How far do you run?” his son asked. Shank answers: “I do sex every day” meaning SIX, as in miles. We were all cracking up.

I called him over to the window to see “the beautiful harvest moon” – it’s huge-ness. He gets up out of the chair, looks at it and starts telling me how it is the satellite thing that goes over and gives us tv signals.

As people age, I am told that we become more of what we already are (i.e., If he was always a grumpy man, he will be more of a grumpy man; if she was always a sweet woman, she may be sweeter yet). I found that the degeneration aged Shank but he was still the very gregarious, easy going, people person he always was. He was talking with someone at the nursing home one day when I visited him (“talking” being in its loosest meaning), as he turned to let the man know I was his wife (always the respectful man). Although I’m only in my early fifties, and told I look younger, the man said to me, “you’re 69, right?”. Shank is nodding complete agreement, while two of the nurses are watching. I said “sixty-nine? …yes, and don’t i look damn good for 69!”. I am certain Shank didn’t understand AT ALL, but when I burst out laughing along with the nurses, so did he. He just always made people around him comfortable.

The move to the nursing home was very difficult and only a last possible resort once it was clear he couldn’t be at home any longer. Shank’s brother and I had convinced him that he worked at the nursing home in order to make that transition smoother and help him understand why he needed to be there. One day while we were both visiting during our lunch hour Shank said “they don’t pay me”. I looked at him and said “yes, but they feed you” and his brother chimes in “so they are losing money”! As we laughed so did Shank. Even if he didn’t get it, or could have taken it personally, his getting along nature persevered. It was a light moment during a very difficult time.

The most hilarious story I can recall is when we were out walking the dogs on a path near our home. Shank loved his dogs, particularly his dog Molly who was his running partner for years. On this particular day Molly was slightly ahead of us, watching out for her man and she came across a toad on the path. She used her nose to push him off to the side, perhaps so we wouldn’t walk on him. I said to Shank “did you see that”? Molly nosed him right off the path!” Shank’s reply: “Molly knows him?” I nearly fell over laughing.

I choose to remember the funny things, and the true loving nature of my husband rather than the way the disease robbed him of his life.

The following is an essay written by Shank’s stepdaughter Andrea prior to his death:

The first thing my mom told me about my future stepfather was that he was a runner. She knew that this one fact could forever alter the way I, in my teenage contempt, viewed him, and she was right. One of our first encounters was a 5-mile run through the trails near my house. I pushed hard up and down the hills, trying to test his endurance to see if he would respond. He did just that, and as we neared the end of the run the trail opened up to a paved road, about 300 yards from the parking lot. “Let’s go, pick it up!” he told me, starting his sprint. I responded and kicked it up a notch, running neck in neck with him before passing in the final 50 yards. By then it was a done deal- he had my stamp of approval.

Three years later Shank and my mother were still dating and our relationship had grown to include long runs together on weekends and discussions about training, nutrition, injuries and racing. It was fall and I was away at college when Shank informed me that the ½ marathon I had agreed to run was, in fact, a full marathon and he had signed me up because he knew I could do it, even if I didn’t think I was ready. He was right about the latter. I was terrified of the 26.2 mile distance.

We ran together for the first 18 miles. We dissected what we were eating and drinking, how our legs were feeling, how our minds were dealing with the race. This was Shank’s 10th marathon and his experience showed. We were complete contrasts to each other; he was calm, soaking up the moment and I was terrified of “the wall.” At mile 18 Shank started to cramp, but I was feeling good. He told me to go on ahead and just take it easy, wait for the wall to come and then fight through it and finish. I didn’t want to leave him behind, but as he stopped to stretch and walk I knew that if I stopped that might be the end of me. The next 8+ miles were magical:I barely felt my legs, the miles kept clicking by and before I knew it I was at the finish line of my first marathon. It’s probably true that eventually I would have run a marathon on my own, but his faith in my ability and his presence through the first 18 miles made it that much more special.

Fast-forward 3 years. Shank is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, a possible outcome of the numerous concussions he suffered as a college football player. For a while after the diagnosis he continued to run, but as time passed he stopped going. Possibly he is afraid of getting lost, or maybe he thinks he has already gone running. He occasionally works out on a treadmill, but still fills out training logs as if he is still running 30-40 miles per week. It’s heartbreaking to see this degeneration of a person, and for me a running mentor. But I have learned that where there is sadness, there can be joy.

Although Shank no longer competes in races he is still an important part of my running success. I feel that in a way, I run for him, too. When I have a good race, I call to let him know and I seek his approval of my training methods and race strategies. He has been present at my past two marathons, and though he has trouble communicating his feelings I can look in his eyes and I know that he still gets it. His body may disagree but his mind knows I am a runner. I don’t know what the immediate future holds for Shank, but I do know that I will continue to run and count my blessings for having had the chance to run those 18 miles together. Each time I toe the line he’s in my thoughts.

Madigan Paradis, Sheldon Paradis’ granddaughter, interned for CLF in summer 2022 as a tribute to her “Grampy”’s legacy. Madigan wrote an update to Sheldon’s Legacy Story as part of her internship.

By Madigan Paradis

Although I did not know my Grampy for much of my life and do not remember many interactions with him, his life has had an indirect impact on mine. He passed away when I was eight, giving me only a few very vague memories of him. However, I have heard enough about him to understand the memories I had with him and why they did not make sense to me at the time. He was diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer's before I was born and had been affected mostly in his speech skills and mood. As a young child, I remember being so confused when he talked and did not understand why he was different from everyone else. The only real memory I have with him was sitting in his kitchen and him teaching me how to eat string cheese. That memory stands out to me because there was no need for any verbal communication, we could understand each other, and I could learn from him without his disease getting in the way. He was smiling and laughing, and it was a successful nonverbal interaction. From what I knew at the time, he was a kind and gentle man who struggled with himself and his relationships with others.

In the years after his death in 2008, I slowly learned more about him as a person from my dad, nana, aunts, and uncle. I learned how he struggled with mood swings all throughout their lives too and he would lash out for no apparent reason. There was something not right with him, but no one understood why. He married three times in his life and had four kids between two different marriages. There seemed to be some inconsistency in his life, and he had difficulty maintaining relationships. He often had sudden raging episodes where he would break things and say hurtful words to the people he cared about. According to my family, his behavior made people fearful to be near him at times. No one could figure him out or understand his erratic behavior. This all took place years before people understood CTE and his official diagnosis of early onset Alzheimer’s Disease.

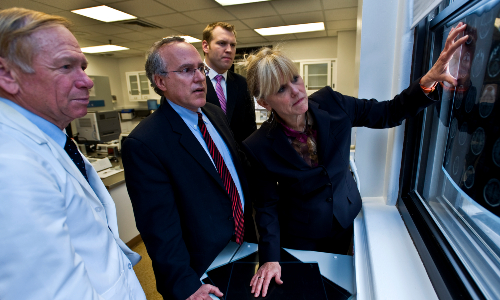

Growing up, my dad often spoke of how he played D1 college football the same way my Grampy did. My dad would bring up the many head injuries he had, as well as how many my Grampy presumably had too in his football career. My nana even remembers old conversations between my Grampy and his teammates, where they would laugh about how many concussions they had. Back then, nobody understood the dangers that would lie ahead. In my sophomore year of high school, I suffered from a serious concussion playing soccer. I remember receiving advice from my Aunt Lisa who was previously involved in some work at CLF, after my Grampy’s brain donation. When I recovered from my concussion, my interest in the subject was piqued. I began to think about how if my concussion impacted me that much, how so many repetitive head injuries could have affected my grandfather, and how could it have affected the way he was throughout his life.

I began to pursue a major in neuroscience in college and reached out to CLF, hoping to become involved. I wanted to figure out why CTE and concussions have such an impact on people and their behavior. Although I did not know my Grampy well or for much of my life, his story has inspired my life and career goals. Many of my family members, including my dad and siblings, have played or still play college sports. I hope to become involved in studying CTE and concussions to help their futures. There was a trickledown effect from the CTE my Grampy had, as it affected the peace of the whole family and has had an impact on many family members. To be a part of his legacy and become involved at CLF has been such an honor and has made me more excited for the future and how I can work to prevent the damage concussions and CTE can cause.

You May Also Like

Living with suspected CTE can be difficult, but CTE is not a death sentence and it is important to maintain hope. Find out how.

Living with CTE

Although we cannot yet accurately diagnose CTE in living people, a specialist can help treat the symptoms presenting the most challenges.

CTE Treatments