Legacy Stories

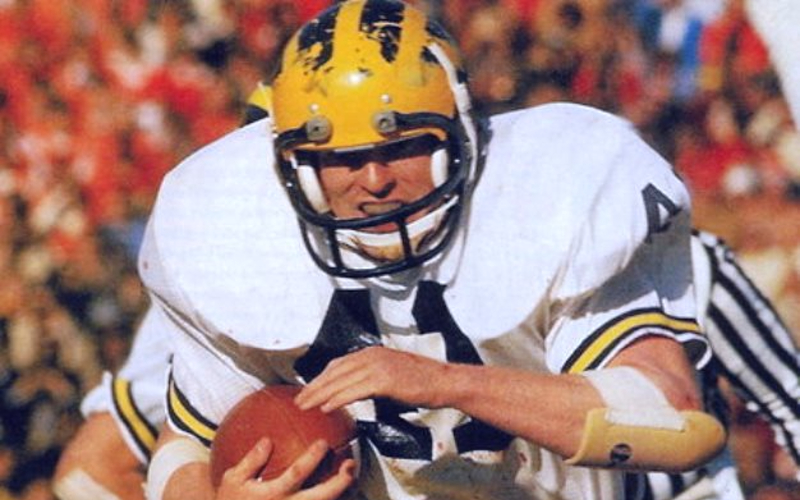

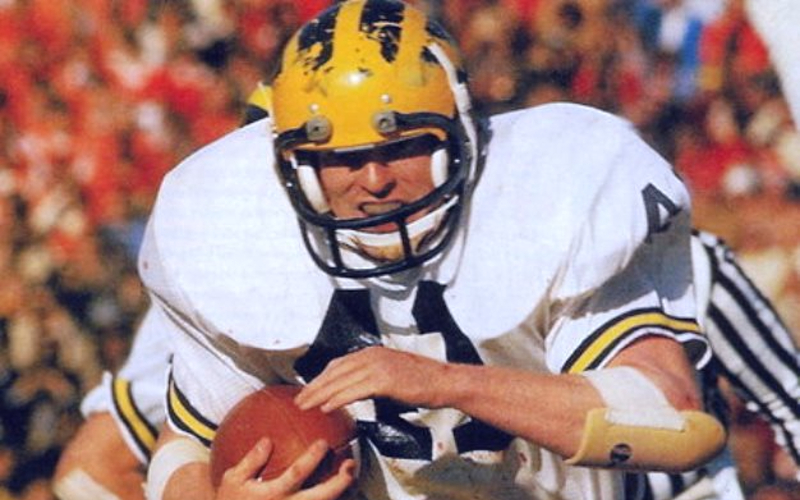

Rob Lytle

Rob Lytle was a prolific running back for the University of Michigan and the Denver Broncos. Lytle was a part of three Big-10 championship teams and was enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame in 2015. Lytle estimated he suffered at least 24 concussions in his career. As Lytle got older he began suffering physically and started having issues with his memory in addition to crippling headaches. Lytle passed away on November 20, 2010 from a heart attack at age 56. After his death, his family donated his brain to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank where doctors and researchers diagnosed him with moderate to severe Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

By Tracy Lytle,

Adding 11 + 20 + 10 gives you 41. My husband, Rob Lytle, wore number 41 on the football field for the Fremont Ross Little Giants, Michigan Wolverines, and Denver Broncos. He wore it in the Rose Bowl and the Super Bowl. Rob died on November 20, 2010. How heartbreaking that he would die on this day.

The events of that day weigh on my heart. Our daughter, Erin, and I were shopping in Columbus. I had left Fremont—the small Ohio town where Rob and I lived—in the morning before Rob was awake. Never a morning person, lately rising from bed and starting a new day had become almost more than he could bear. While leaving town, though, I realized I had forgotten something. At home, I caught Rob freshly awake and struggling to walk down the stairs. As he descended the stairs, I watched his knees refuse to bend. He leaned against the railing, which strained and wobbled loose from the wall, failing against the weight of supporting my suffering husband. Rob grimaced. His many years of football had devastated his body. My heart winced.

Knee operations in the teens had led to an artificial left knee and multiple shoulder surgeries had led to an artificial right shoulder. Rob had mangled fingers that pointed in all different directions. He suffered from vertigo, incessant migraines, and eighteen months earlier had survived a stroke. In recent months, his mood had soured and his spirit seemed beaten. He was distant and depressed—forgetful and lost in our conversations—a cloudy shade of the man I had loved for forty years.

Standing together in the kitchen, Rob prepared to devour a breakfast quiche of eggs, cheese, and sausage. I fussed with a Christmas setting on the table. Just the night before we had carried eight loads of Christmas decorations down three flights of stairs while carols sang on the radio in the background. I kissed Rob goodbye before his first bite, not realizing that this would be my last contact with him.

Every moment in life is precious.

While shopping, Erin and I got the call that Rob had had a heart attack. Life flashed before me. I saw our first kiss and first dance, our last fight and last hug. Was Rob alive? The doctors wouldn’t share anything over the phone. I prayed, wept, and hoped as Erin drove us two hours north from Columbus to Fremont.

Once at the hospital, Erin and I were joined by Kelly (Rob and I’s son). A young doctor ushered us into a conference room. I will never forget the sight of my children falling to the floor in anguish as we heard the news. Our Rob—my Rob—had died. They had just lost their hero, and I had just lost my husband.

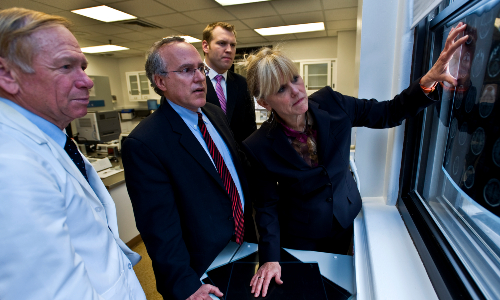

The next day, the Concussion Legacy Foundation, then the Sports Legacy Institute, called and asked if we would donate Rob’s brain for their research on head trauma. I had never heard of them or the cause before the call. Rob played in an era when a concussion meant only that you had had your bell rung and where the first fix for an injury was to rub some dirt on it while the second was a series of painkilling injections.

Still, Rob had mentioned many times in conversation that he suffered at least twenty-four concussions that he remembered during his career. One stood out, and I can remember us laughing about it. In 1978, during the AFC Championship game versus the Oakland Raiders, Rob had smashed into Jack Tatum near the end zone and fumbled. Except the referees disagreed and ruled that Rob was down before he lost the ball. Oakland coach John Madden fumed it was a fumble and sprinted along the sidelines screaming at officials. Denver scored a touchdown on the next play, won the AFC title, and played in Super Bowl XII.

In our talks, Rob had told me he didn’t know what happened on the play because he had been “out cold.” He also admitted that he remembered little of the AFC Championship because of the concussion he suffered versus Pittsburgh one week earlier. “I had to play, Tracy,” I can remember Rob saying.

Never did I think that all these concussions could have caused Rob’s changing personality. Rob and I recognized how football had abused him physically and emotionally. What we never realized was the mental destruction the game caused. After the Foundation studied his brain, doctors diagnosed Rob with moderate-to-severe CTE. They told us it was a “miracle” that Rob held a job and functioned in society given the advanced state of his brain’s decay. They were shocked he had been able to mask his suffering. Rob’s somber mood, mental fumbles, issues remembering dates, and recent withdrawn personality came into sharper focus. Before this moment, we had not realized the connection between these problems and football.

Rob’s years of repetitive, violent collisions on the football field had caused CTE. And CTE had caused the change in my best friend of forty years.

Rob was a Fremont Ross Little Giant both on the track and football field where he dreamed as a little boy of becoming a professional football player. We had known each other since 7th grade, but it was while running track our junior year of high school that our lives intertwined. I was captain of the girls’ team, and Rob was the star for the men. During practice one afternoon, the girls were short a starting block and needed to borrow one from Rob. Easy enough. Except everyone was afraid to approach him. He was the star, the fastest on the team, and his sometimes-brash mouth plus the “don’t mess with me” scowl he wore when competing intimidated most.

Not me. When I asked if we could use his starting block, a smile spread on his face and his eyes softened. “Of course,” he replied, and our friendship began.

We dated through high school, spending nearly all our time together. Rob gained over 2,500 rushing yards for Fremont, and in 1972 the Ohio United Press International and Associated Press voted him all state. Coaches from colleges across the country sought Rob’s services. They even knew to call my parents’ house when they needed to find him.

I remember winter nights when the two of us would be outside laughing while digging tunnels or building forts in the snow outside my house. The phone would ring inside as recruiters called to make their pitches, and my mom would holler at us from the window. “Tell them to call back,” Rob would say and laugh. I suppose I could have known then that for him family would always come first.

Rob narrowed his college choice to Ohio State and Michigan—Woody Hayes and Bo Schembechler. Woody would visit Fremont and sit with Rob for hours talking Civil War history and military strategy, favorite subjects for each. He told Rob that he could play as a freshman. Bo said simply: “You’ll never be as great as you are right now. We have six halfbacks already at Michigan. If you come here, you’ll be number seven. Anything that happens after that is up to you.” Instantly, a father-son relationship developed between Rob and Bo.

Rob and I attended Michigan together. When I moved in, several older girls laughed when I told them that my boyfriend played football. “Won’t be your boyfriend for long,” they scoffed. “Good luck,” they mocked. I guess we proved them wrong.

While at Michigan, Rob was a member of three Big Ten championship teams. He ran for 3,317 yards and scored 26 touchdowns. Rob currently ranks 8th in rushing yards in school history and 11th in all-purpose yards with 3,615 on 579 touches. As a senior in 1976, Rob ran for 1,469 yards, was named first team All-American, and the Big Ten’s Most Valuable Player. He finished third in that season’s Heisman Trophy balloting behind Pittsburgh’s Tony Dorsett and Southern California’s Ricky Bell. In 2015, the National Football Foundation inducted Rob into the College Football Hall of Fame.

Before his senior, All-American season, Bo asked Rob if he would play both fullback and tailback—requiring him to sacrifice carries, yards, and a shot at the Heisman Trophy—so they could maximize their talent on the field. Rob made the switch willingly. Michigan led the nation in total offense and won the Big 10 championship that season. Bo always preached, “The team, the team, the team.” Later, Bo would state many times that he felt Rob was the best teammate and toughest player he ever coached—perhaps the greatest praise Rob received for playing football.

Humility, self-sacrifice, and putting teammates above himself mattered to Rob. He loved football and lived to play the game.

We married on June 3, 1977, in Fremont. Since Rob was drafted in the second round by the Denver Broncos, we moved to Denver to begin our lives. Rob was fortunate to spend all 7 years of his professional career with Denver. As a rookie, he scored a touchdown in Super Bowl XII. Even though Denver lost to Dallas, it was an exciting moment in our lives.

While a Bronco, Rob worked at Cotrell’s Clothing Store in the offseason and involved himself in many charities. He served as honorary chairperson for the Listen Foundation, worked with the United Way, and helped with the Special Olympics. He was a fixture at fundraisers during those years.

Injuries filled Rob’s professional career, and it seemed we lived in operating rooms and hospitals. He always worked to overcome them, though, and return to the game he loved. Still, the body—and mind—can only bounce back so many times before it screams no more. In 1984, Rob’s final knee operation was more than his body could conquer. While playing for Denver, Rob scored 14 career touchdowns and ran for 1,451 yards to go along with 562 receiving yards. He reached the pinnacle of his profession, but left regretting that injuries kept him from ever playing to the level that he knew he could reach.

We returned to Fremont in 1984, where Rob worked in his family’s 5th generation men’s clothing store. Retirement was difficult for Rob. Though his heart longed to continue playing, his body could no longer take the physical toll of football. On many nights in the first years after leaving football, we would retreat to the couch after Erin and Kelly had fallen asleep and Rob would sob as I held him. He missed football, but even more he missed the purpose and direction the sport gave him. He believed that he had failed, despite playing seven seasons in the NFL, because he never achieved the impossible goals he had for himself. Over time, we put the pieces together, but Rob’s longing for the game never faded.

Rob closed his family’s store in 1989, and then worked for Bowlus Trucking and Turner Construction. Rob later became involved in the banking business and was vice president and business development officer for a regional bank in Northwest Ohio when he died.

During these years, Rob was a wonderful father and friend. We spent every Sunday with Erin, Kelly, and friends in some pick-up game of softball or football. The lasting memory of Rob for so many people is seeing him with a big smile on his face, surrounded by laughter, and immersed fully in a game or activity with his kids.

Once again, Rob became involved in the community. He was a Rotary president, YMCA board member, and assistant football coach. He served on the board of his favorite organization, the Sandusky County Board of Developmental Disabilities, and they even named their new facility after him because of all the support he gave.

Rob was blessed with a kind and genuine spirit. He invested himself in helping others, and lived his life filled with passion. Rob always wanted to make a difference in people’s lives while striving to include them and put a smile on their faces, which he could almost always do thanks to his sense of humor. Rob believed that every person was important and had a story to tell. He taught our children to be kind, considerate, compassionate, and to care for others. Rob filled our children’s hearts and minds with pleasant memories of meaningful times spent together.

We remember Rob as a loving father who shared the fun and pain of raising a family. Rob always listened, loved, and helped. More than anything else, he loved his family.

Rob wasn’t perfect, but he tried with everything he had.

You May Also Like

Living with suspected CTE can be difficult, but CTE is not a death sentence and it is important to maintain hope. Find out how.

Living with CTE

Although we cannot yet accurately diagnose CTE in living people, a specialist can help treat the symptoms presenting the most challenges.

CTE Treatments