Legacy Stories

Richard Pickens

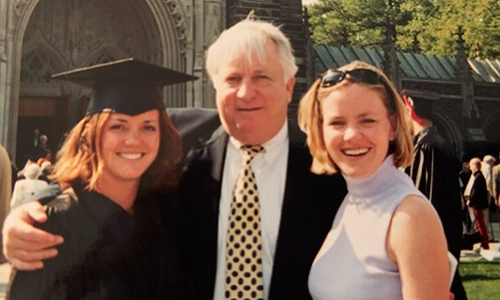

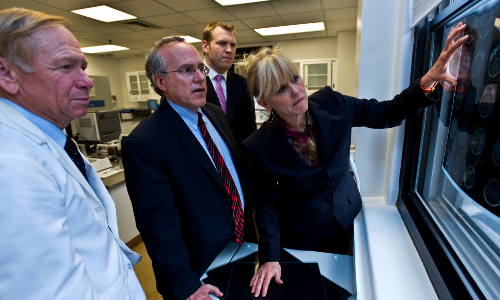

Richard Pickens was a prolific fullback at the University of Tennessee in the late 1960’s. After football, his fits of rage caused his family to live in a constant state of fear. Pickens’ memory and executive functioning began to decline in his 30s. By his 50s, he began to lose his cognitive, behavioral, and motor functioning. After his death in 2014 at age 67, his family honored his wish to donate his brain to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank. Researchers there diagnosed him with Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) and motor neuron disease. Five years after his death, his daughter Sarah hopes sharing his story will help educate others on the potential effects of CTE on former football players and help move towards a world without CTE.

By Sarah Pickens, Richard's daughter

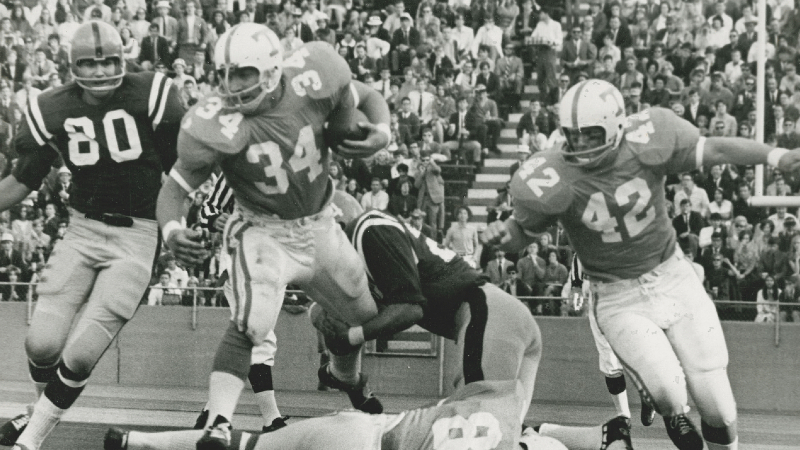

My father was a strong physical presence. He was shorter, but thick and muscular. My body tends to reflect his. My older sister and my childhood was filled with waterskiing, fishing, tubing, and attending University of Tennessee football games. As a young soccer player, I would challenge my father to races next to our grandmother’s garden, on a football field, from one tree to the next, and he would always make sure he won. He was a football prodigy in his hometown of Knoxville, Tennessee, where football was king. He played high school ball at Young High School and had an outstanding career with the beloved Tennessee Volunteers, coached by Doug Dickey. Wearing #34, he played in the ‘66 Gator Bowl, ’67 Orange Bowl, and ’68 Cotton Bowl, and won the All-SEC Fullback of the Year award in 1968. After his career at UT, he made the preseason team for the Houston Oilers and was later inducted into the Tennessee Sports Hall of Fame.

Dig deeper, though and there is an uglier, more painful layer to my father’s story. His time with the Oilers ended after he lost his temper with his coaches. He exhibited tantrums on the sidelines of my college soccer games at referees or players, which always embarrassed me.

In our personal lives, while our childhoods had glimpses of happiness with our father, cracking jokes over “RC Colas and moon pies,” using his video camera to make our own fishing shows, and eating his famous steak and mushrooms, we were always nervously anticipating the next violent episode. We closed our eyes and held tight while he drove recklessly with us in the car. We locked ourselves in bathrooms, or frantically packed our things to jump in the car and drive away. We never knew when he would erupt.

When we were old enough to understand, and long after our parents divorced, we attached this behavior to his alcoholism and anger management issues. We later realized, though, there were confounding issues.

My dad’s playing career included close to 200 concussions by his estimation. After his death in July, 2014, we donated his brain to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank, where scientists confirmed primary diagnoses of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) and motor neuron disease associated with CTE. His substance abuse was a contributing diagnosis.

The symptoms of CTE can be expressed erratically, including violence, mania, depression, dementia, among others. Once a physical presence, my father was reduced to stumbling across the room, shuffling his feet and holding onto furniture because he was too stubborn and proud to use a walker. He liked to refer to his debilitation as a “hitch in his giddup.” In addition to his outbursts and aggressive behavior, he developed difficulty with concentration and organization in his 30s. By his 50s, he suffered from language difficulty, weakness in his legs, and progressive decline in his behavioral, cognitive, and motor functions. He was misdiagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s Disease, to which my sister organized a team in his honor for an ALS walk. The diagnosis, for a variety of reasons, didn’t quite fit, and was changed to Primary lateral sclerosis (PLS). Once again, he was misdiagnosed. He was losing his mental and physical capacity, and he didn’t know why.

As his symptoms progressed, the glimpses of happiness we once saw of our father in childhood lessened. We knew our visits with our father must not exceed 36 hours, or we would tumble into dark topics of despair. We brought lists of uplifting topics and stories to share, my sister playing the soothing, empathetic nurse, and I would operate as the ultimate jokester. Once, as a 20-something, I broke our golden rule and extended beyond a 36-hour visit. He attempted to physically attack me, but I was fresh out of college and fast as hell. He was reduced to holding onto furniture, shuffling his legs, lest he might fall. From that moment on, I broke communication with my father.

My sister and mom gave me updates on his condition from then on. He moved into a nursing home after totaling his car. He showed Sundowning behavior often, and his drinking contributed to him dying, with lots of life to live, at age 67.

In his nursing home room there was a display case with one of his Vol helmets, boasting a deep crease from a violent collision at Neyland stadium. My father’s football friends rallied around him, taking care of him, his finances, and his funeral, as he refused our help. Even though we now know his football career caused him so much pain, my father requested for his football friends to spread his ashes where he once played the game he loved.

I share this version of the story to shed light on the very real narrative of a man whose life was stolen by the decay of his brain. While parents continue to send their children out on the field in helmets and pads and memorize stats to draft their favorite players to their fantasy team, I believe CTE becomes something easier to ignore than to recognize. CTE is a hindrance to our culture’s Saturday and Sunday (and Monday and Thursday) pastime. This year marks the fifth anniversary of my father’s death, and I am at peace with the chaos and destruction my father caused on our lives. I am beginning to fondly remember the happy times with my father when he was free from the hold of his confounding diseases. And I am hopeful for continued progress on the efforts to combat the fatal impact of CTE.

You May Also Like

Research is core to everything we do. Explore different research studies to learn more and see if you or a loved one would be a good fit.

Participate in Research

We encourage everyone to pledge to donate their brain to research. Learn more about our CLF Research Registry and how you can sign-up to give back through science.

Pledge Your Brain