Legacy Stories

Fred Smith

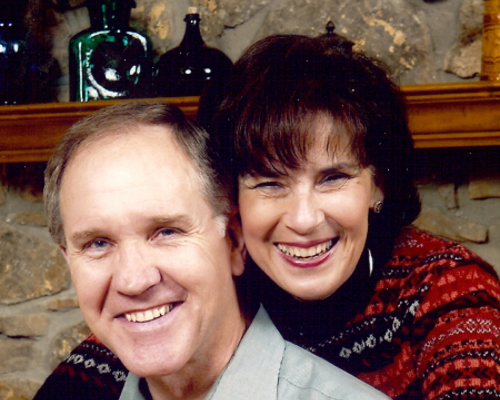

Fred Smith was a high school and college football player and a U.S. Army Veteran. He played at Elkton High School in Maryland and for Virginia Military Institute before a 10-year career in the Army. After the military, Smith had a 20-year career in sales, where he worked his way up to a manager position. Late in life, Smith became unusually angry, hostile, and lost his executive functioning skills. Smith passed away at the age of 66 in 2011. After his death, researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank diagnosed him with Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). Smith’s wife, Linda, shares his story to put a face to the degenerative brain disease.

By Linda Smith, Fred's wife of 43 years

Fred, my beloved husband of 43 years, was an awesome husband, father, grandfather, and friend. To us who loved him, he was extraordinary. But in his love for playing the game of football, he was quite ordinary and like so many other men and boys.

It is my hope that Fred’s story will give another human face to CTE, the devastating, but preventable, dementia caused by head trauma. I hope that Fred’s story will encourage parents, coaches, players, and medical professionals — whole communities — to support the work of the Concussion Legacy Foundation and the BU CTE Center. And, finally, I hope his story will help former players and families struggling to find answers to bewildering changes.

CTE caused my Fred to change so subtly and so slowly, but so remarkably, over time that it’s hard to remember the Fred of our beginning and impossible to pinpoint the moment CTE laid its claim.

Fred and I met in college, the unlikely story of a blind date going well. . . his roommate dating my roommate. We were Navy brats who shared a love of traveling. We raised two fine sons, Shayne and Jeremy. We were supported by family and blessed to gather lifelong friends along the way, many attracted by Fred’s warmth and humor.

Anyone who met Fred for the first time knew immediately that he loved people. He drew people to him with his mischievous sense of humor, wry smile, and pranks. He never failed to bring a smile to those he lured into his practical jokes. He was fun and could engage strangers whether in a village along the Amazon or in a checkout line at Kroger’s. Who else could entice a couple on the eve of their wedding to abandon their wedding party to join us strangers for a few hours of laughs? He was the proverbial “people person.“ Fred’s humor drew people to him, but his honesty, compassion, and unpretentiousness kept them there.

Typical of many boys, Fred grew up with a love of sports, particularly football. At Elkton High School in Virginia, he played football (All-State), basketball, baseball and track. At Virginia Military Institute he played left tackle on the football team for four years. He said he went to college to please his parents, but stayed to play football. He shrugged off “getting his bell rung” as just part of football. In a televised game, he was taken from the game after a hard hit and returned minutes later. . . but joined the huddle of the opposing team. A picture of this play in a local newspaper is a haunting reminder of that day. Once seen as a humorous memory in his mother’s scrapbook, it now represents the kind of hit that had potential long-term consequences.

After graduating from VMI in 1969 with a B.A. in Economics, Fred served as an Army Field Artillery officer for 10 years, beginning with a tour in Vietnam where his men would later describe him as a respected leader: caring and calm under fire. These qualities were used to describe Fred repeatedly throughout his military career. Fred’s last assignment took us to Germany where Fred jumped at the opportunity to join a rugby team. The oldest and least experienced on the team, he played with fervor and enthusiasm but, unfortunately, in the style of football which led to several concussions.

In 1979, Fred left the Army to pursue a new career in sales. During the next 20 years, he worked for several companies in the paper industry, and eventually worked himself into management.

Along the way, there were nagging concerns about very subtle changes in judgment, temper, and confusion in doing seemingly simple tasks. Things just didn’t seem right. And Fred’s long history of headaches seemed to worsen.

Gradually, the early hints of something wrong evolved into serious mistakes, hostility to those whom he disagreed with and confusion, particularly in math, problem solving and organizing. He had trouble writing coherently, learning new computer software, and using his cell phone. He began having night terrors and would yell out that people were trying to get him. Early neurologists and imaging found nothing wrong. . . and, as we would be told often in the coming years, his “memory” was great.

In the last two years that he was employed, Fred was demoted from general manager to sales manager to salesman, and finally to dismissal. Confusion and inappropriate responses in interviews cost him any chance of getting another job. Neurologists attributed these changes to depression from losing his job, but antidepressants didn’t stop the declines. Fred recognized that he had trouble with word finding and with learning new things, but rejected any other suggestion of personality change.

The night terrors and an obsession with watching war movies took us to the Veterans Administration in 2006 where Fred was screened for PTSD. Fred’s ability to communicate and remember events 36 years in the past were iffy at best by then, so the screener did not see PTSD; but he did see that something was definitely wrong and suggested more testing. After years of searching for answers, Fred received a tentative diagnosis of a dementia that, like CTE, begins with behavioral and personality changes. By this time, Fred’s mounting frustration turned to frequent angry outbursts.

When research started emerging about a kind of dementia that could be caused by concussions and repetitive hits, something clicked. Was it possible that Fred’s years playing football and rugby had caused his dementia. CTE wasn’t a dementia Fred’s early neurologists recognized as a possibility. And I was initially skeptical, too, since most of the first cases of CTE had been found in elite professional athletes, athletes who had played much longer and at a much higher intensity than Fred had. After all, if Fred did have CTE, how many thousands of Freds could be out there. What a truly horrifying possibility!

The boys and I needed to know the truth, and I was absolutely certain that Fred would want that too, so Fred became part of the Concussion Legacy Foundation and BU CTE Center brain donation program.

CTE took Fred little by little, one ability after another. It was especially hard on him because he understood on some level and was often scared. He knew us to the end even though he had lost his ability to think, talk, and walk. I miss him terribly, but know how blessed we were to have had so many years of fun, adventure, and love, the memories of which will last a lifetime. And although our grandchildren never got to know their fun and loving grandfather, I am comforted knowing that the best of Fred lives on in our sons.

As hard as his illness was, the confusing years searching for answers and then the heartbreaking steady declines, the real tragedy was that Fred’s death from CTE was totally preventable.

Those of us who loved Fred are comforted that Fred’s death and story may help researchers learn more about CTE. . . Perhaps to find markers and educate doctors which will lead to earlier diagnoses and thus shorten the anguished years of not knowing. Perhaps to sound the alarm about the potential epidemic among us. . . Perhaps to alert parents, players, and coaches of youth contact sports to listen to the research. . . and perhaps to save another typical young person from living Fred’s story.

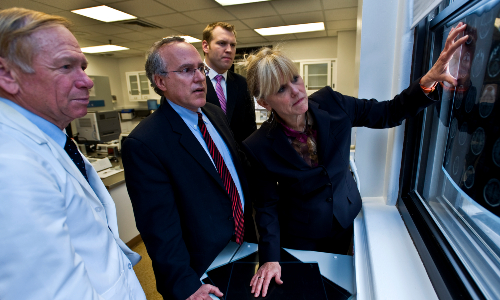

I can’t thank the researchers at the Concussion Legacy Foundation and BU CTE Center enough. Their dedication not only for uncovering the depth of the problem but also for searching for solutions is inspiring. Thank you, Dr. McKee, Dr. Stern, and Chris Nowinski and the staffs at CLF and BU for giving Fred’s family and friends the peace of finally knowing and the opportunity to help others.

You May Also Like

Although we cannot yet accurately diagnose CTE in living people, a specialist can help treat the symptoms presenting the most challenges.

CTE Treatments

Those struggling with suspected CTE are not the only ones who need support. View tools and resources for CTE caregivers.

Caregiving for CTE