Legacy Stories

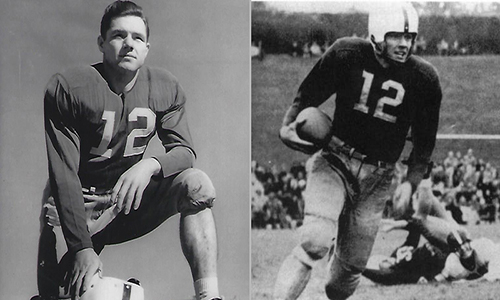

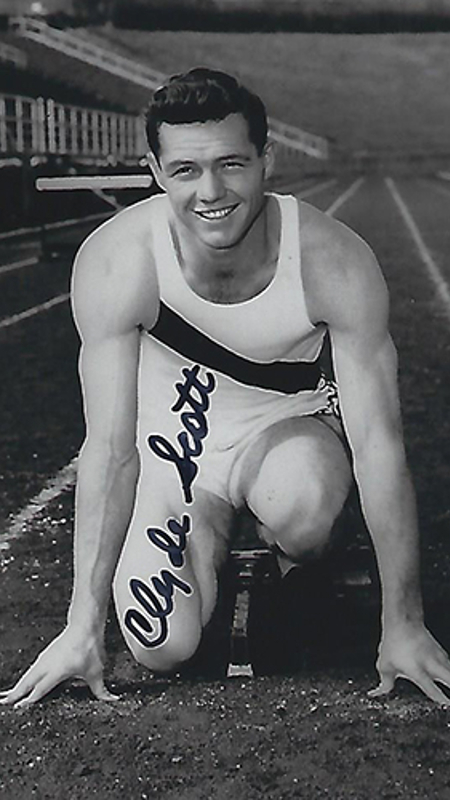

Clyde L. Scott

Clyde Scott was a world-class athlete who was named Arkansas’ Athlete of the Century in the 1900’s by the Arkansas Daily Gazette. Scott was an All-American at the U.S. Naval Academy and the University of Arkansas in both track and football. He went on to hold two world records in track and was a first round NFL draft pick by the Philadelphia Eagles. As Scott entered his 80s, he became paranoid, suffered from hallucinations, and was diagnosed with dementia. After his death at the age of 96, researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank diagnosed him with stage 4 (of 4) Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). Steve Scott wrote his dad’s Legacy Story to honor his incredible life and share what being apart of CTE research would have meant to Clyde.

By Steve Scott, Clyde's son

My father Clyde Scott was an extraordinary athlete who lived a long and productive life. He died in 2017 at the age 93 after a long battle with dementia. After his passing, we were surprised to learn that he was diagnosed with Stage 4 (of 4) CTE.

In February 2000, the state’s largest newspaper The Arkansas Democrat Gazette declared Clyde Scott Arkansas’ Athlete of the Century (1900 – 1999). They called his sports resume impeccable and undisputable. It is easy to see why.

Clyde was an All-American at two universities and at two sports, held two world records in track, won a gold medal at the NCAA championships, a silver medal at the 1948 London Olympics, was a first round NFL draft pick, played four seasons and was on two World Championship teams (1949 Eagles and 1952 Lions). He was considered one of the greatest athletes of his time.

Clyde was born August 29, 1924 in Dixie, Louisiana, the third of ten children. His dad was an oil field worker. Clyde first gained notoriety in high school on the football field, but he also ran track where he set a number of state records. In the summer, he played baseball which he always considered his best sport. The St Louis Cardinals offered him a contract his senior year. Clyde loved baseball but wanted to go to college.

With the help of some businessmen in his home town, he received an appointment to the US Naval Academy. He played football for the Midshipmen in 1944 and 1945 and was named a second team All-American in 1945. At the time, Navy was the second best team in the country. He also ran track at the Academy where he set Academy records in the 100 dash, 220 low hurdles, 110 high hurdles and the javelin. In 1944 and 1945, he was the Academy’s undefeated light heavyweight boxing champion.

After football practice one day in 1945, Clyde had the good fortune to meet Miss Leslie Hampton from Lake Village, Arkansas. She was the reigning Miss Arkansas visiting the Naval Academy for a tour. His roommate was scheduled to be her escort but was called away on a cruise and Clyde was asked to fill in. They met, fell in love, and decided by the end of the school year they wanted to get married. With the war having ended, Clyde made the decision to resign from the Academy. That summer he was visited by coaches from around the country including Bear Bryant at Kentucky and Johnny Vaught at Ole Miss. He was recruited to come to the University of Arkansas by head coach John Barnhill, where he ultimately decided to continue his football career. The fact that his bride-to-be was attending the U of A may have influenced his decision to join the Razorbacks.

At Arkansas, Clyde was named All-Southwest Conference in 1946, 1947 and 1948, a second team All-American in 1946 and a first team All-American in 1948. His jersey number 12 was retired after his graduation. Clyde also wanted to play baseball, but his coach would not allow it. He did permit Clyde to run track where he set school records in the 100-yard dash, the 220 low hurdles, the 110 high hurdles, the 440-yard relay, and the javelin. In the 1948 NCAA Finals he tied the world record in the 110 high hurdles with a time of 13.7 seconds. That summer he made the U.S. Olympic team in the 110 high hurdles and went to the 1948 London Olympics where he won the silver medal in a very close finish.

Clyde was drafted in the first round of the 1949 NFL draft by the Philadelphia Eagles. He played three seasons with the Eagles and one season with the Detroit Lions. He battled injuries throughout his professional career and was forced to retire after the 1952 season.

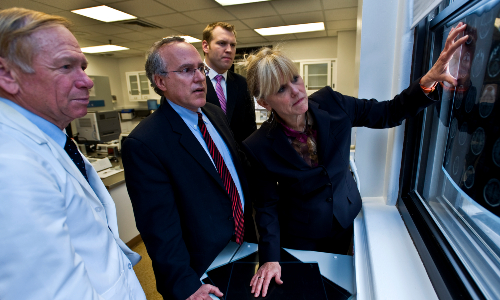

Having lived such a long life, my dad would seem to be an unlikely candidate for the CTE brain study. His cognitive problems began when he was in his 80’s, much later in life than would be expected. Having a 93-year-old suffer and die with dementia did not seem that uncommon. Credit his wife of 72 years, Leslie, for making the decision to donate his brain to the study. She had seen some press coverage of the CTE study being conducted at Boston University and heard that the researchers were especially interested in brain donations from former NFL players. She realized it was an important study. After talking it over with me and my sister, the family decided to pledge my dad’s brain for research through the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank research registry prior to his death.

After his death, the efficiency of the donor program was very impressive. His brain was in Boston within the first 24 hours. Over the next several months, researchers gathered detailed information on dad’s life and sports career. You could tell that everyone we dealt with in the program was very committed to their work.

It came as a big surprise to the family that the study found dad had stage 4 (of 4) CTE. The reporting doctor said they found evidence of CTE throughout his brain which had also shrunken considerably.

Looking back, we realized there were signs that fit the CTE profile. He did not become aggressive or suffer from depression, but he did become extremely paranoid. For years, he had several irrational fears he had a very hard time dealing with. He hallucinated and had recurring nightmares. It made his life very difficult. It was also very hard on his family, especially his wife. Thankfully, the paranoia went away in the later stages of his dementia.

Dad’s mother lived to be 102 and maintained her wit and intellect to the end. His dad died of emphysema at the age of 96. There was no history of dementia in his family. How many years of meaningful life did he lose to CTE? I suspect a couple of decades but of course we will never know.

Would he have played football if he had known what may be coming? I never got to ask him that question. Football got him out of poverty, gave him an education and helped set up a successful business career, so I expect his answer may well have been yes. I do know he never encouraged me or my son to play football. Would he be glad to be part of this important study that may encourage others to avoid that dangerous path? Knowing what we know today, I have no doubt he would say “yes” to that.

You May Also Like

Living with suspected CTE can be difficult, but CTE is not a death sentence and it is important to maintain hope. Find out how.

Living with CTE

Although we cannot yet accurately diagnose CTE in living people, a specialist can help treat the symptoms presenting the most challenges.

CTE Treatments