Get Inspired

Solving The PCS Puzzle: Lily Winton's Story

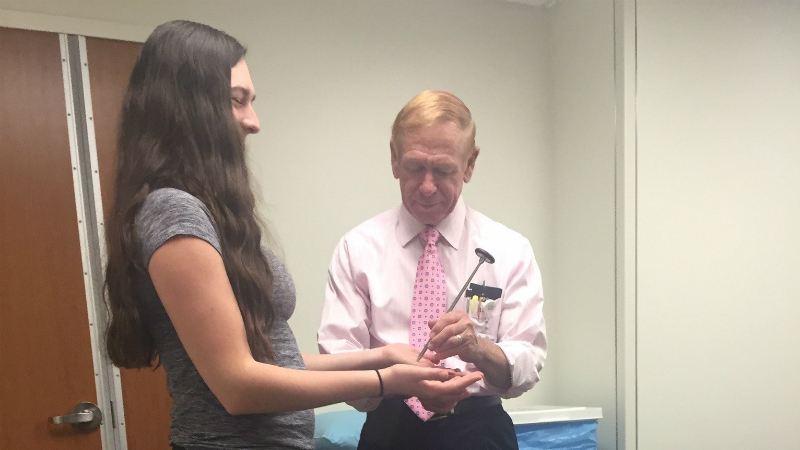

In the summer before her junior year of high school, Lily Winton started experiencing headaches, irritability, and neck pain, seemingly without explanation. While doctors couldn’t find answers, Winton had them all along. She just couldn’t remember. Two months after the tubing accident that caused her third concussion, Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS), and the onset of her symptoms, she started to remember what happened. In this story, Talia Burstein, a human health student at Emory University, shares Lily’s journey with PCS and what Lily has had to do to manage her symptoms and further her recovery.

Posted: April 19, 2017

Talia Burstein, a junior at Emory University, is a human health major who aspires to attend medical school. As president of Emory's Bioethics Society and a diehard Patriots fan, Talia takes great interest in the treatment and recognition of concussion-related syndromes and diseases. Talia interviewed high school student Lily Winton for the Concussion Legacy Foundation in order to better understand how patients manage Post-Concussion Syndrome (PCS).

During the summer going into her junior year, Lily Winton worked as a Counselor-in-Training (CIT) at the sleep-away camp she had attended since she was a child. During the second half of her summer, Lily started to experience headaches. Unable to figure out the source of her headaches, Lily attributed them to heat and dehydration. She slept more than usual and ignored them the best that she could. At the end of summer, despite the increasing number of headaches, sudden irritability, and some new neck and ear pain, Lily continued to train for tennis and prepare for the start of her junior year of High School. She knew the year would be full of hard schoolwork, tennis training, USTA competitions, college tours, and friendships. Lily visited her pediatrician to try to uncover the cause of her headaches. Did she have mono? Maybe Lyme disease? A cardiovascular issue? Her doctor ran many tests, but everything came back normal.

Once school began, Lily began to experience constant, more severe headaches, ringing in her ears, increased neck pain, and short-term memory struggles. When she tried to read, a whirlwind of dizziness and fogginess came over her. Lily just wasn’t acting or feeling like herself. She returned to her doctor to undergo additional testing but to no avail; none of the tests revealed anything abnormal. Despite the lack of diagnosis, which caused grave concern to Lily and her family, the pain of the headaches, and the inability to read with ease, Lily was determined to continue on with her junior year.

In mid-September, Lily forced herself out of the darkness of her bedroom to go on a college tour with her parents. While walking on the sidewalk of a busy Boston street, Lily began to stagger, nearly stumbling off the curb of the sidewalk into a moving car. Her mother quickly snatched her by the collar of her sweater to pull her back to safety. When Lily’s mom looked into her eyes, she knew instantly that something was very wrong. She asked Lily if she had hit her head and at first Lily said no but when Lily’s mom probed her to really think hard, Lily responded with “yes.”

Two months after the incident, the details of a tubing accident she had been in with a camp friend finally began to come back to her. Lily’s mom was able to phone the camp friend and find out the details of the accident.

When Lily was at her summer camp, she and a fellow CIT were tubing (pulled on a raft tethered to a speedboat). The boat driver revved up the engine to approximately 50 mph and took them on a wild ride, where they were whipped around and eventually thrown off the tube and into the water.

“For those of you who have never been whipped off a tube, when you hit the water it feels like hitting a brick,” Lily recalls. Typically, you fly off the tube onto your side but when Lily was thrown off she entered the water headfirst. Colliding headfirst with the lake caused Lily to black out immediately. When she finally came to and was pulled on to the boat, she was holding her head in pain. The boat driver quickly drove the boat back to shore where Lily walked herself back to her cabin and went to sleep. When Lily woke up the next morning, she had no memory of the events of the previous day.

“It was like all of a sudden, all the pieces of the puzzle made sense,” June Ferestien, Lily’s mom, explained.

The puzzle

Every puzzle has multiple pieces and this one was no different. In middle school, Lily was a superstar soccer and basketball player. At the end of 7th grade, she got a concussion. Lily was out of school for a few weeks and was slowly cleared to return to her athletic training once all her concussion symptoms were gone.

On the soccer field five months later, in October of 8th grade, Lily received her second concussion. This time, the concussion was a little bit worse. Lily suffered from worse headaches and nausea, which put her out of school for a month. While she did eventually return to all of her sports and activities, she noticed that headaches would linger slightly longer than usual.

After this second concussion, Lily’s parents decided she had to stop playing contact sports as a third concussion could make things terribly worse.

Lily, a natural born athlete, knew she had to reinvent herself. Looking for a non-contact sport, she took up tennis and grew to become a top player in Massachusetts. She played #2 singles varsity for her large public high school, where she was named Boston Globe All-Scholastic for the Bay State League. Lily had also earned a top 100 USTA ranking in New England.

When Lily went off to camp that summer before her junior year, she had figured out what it took to avoid any more concussions. She avoided soccer, lacrosse, basketball...even diving.

She didn’t know that soft water could hit so hard or that a fun afternoon of tubing could leave her with a hit so severe that she would have no memory of receiving it. So, when doctor after doctor asked probing questions, she had nothing new to reveal about what had happened.

Only when her memory of that summer day began to come back to her months later could she provide the doctors with the missing piece of the puzzle, the forgotten hit to her head. Now, with this new information, Lily finally had a diagnosis for her symptoms: a third concussion causing severe post-concussive syndrome (PCS). Post-concussive syndrome consists of multiple debilitating symptoms that persist long after typical concussion symptoms subside.

The circuitous road to recovery

Discovering a diagnosis was only a small sliver of the battle Lily had yet to face. By this point, she was a month into her junior year. She knew a typical third concussion would have her out for a few months so she took a short term medical leave for the rest of the fall semester and planned to return, good as new, in the winter.

The plan sounded great. Lily would still be able to graduate on time with her friends, return to playing tennis in the spring, and continue with her college search. Unfortunately, Lily’s case of post-concussive syndrome was far from typical. In fact, there is no “typical’ when it comes to concussions and post-concussive syndrome.

Lily’s time off of school was filled with a long and slow recovery. “For months I didn’t get out of bed. I lived with a chronic migraine. I couldn’t walk by myself. I couldn’t go up the stairs. No lights! I couldn’t have a normal conversation with people. I didn’t have my normal feelings and emotions. I suffered from really bad post-concussive syndrome,” Lily recalls. Her journey to recovery was an uphill battle; she got worse before she got better.

Lily frequented the emergency room with horrific pounding headaches that she described as a 12 out of 10 on the 0-10 pain scale. In the emergency room, and during a 4-day hospital stay, she received neck injections that helped ease the pain. In total, Lily had over 80 pain injections in her forehead, neck, and upper back. A normal neck is curved. Lily’s was stick straight. She described, “It looked like there was a metal rod going through it.” The doctors discovered that she had suffered severe whiplash.

While the injections helped relieve some of Lily’s acute pain, which allowed her to be released from the hospital, her overall pain was still unbearable. No medicine would work to treat the more than 30 symptoms she had been experiencing.

For her inability to sleep, she tried melatonin. No luck. When she could bear the light and tried to read, her right eye, which corresponds with the side of her head she hit, would not converge in the same way as her left eye. This made it impossible to read without blurriness and dizziness. She also suffered from saccadic eye movement, which prevented her eyes from tracking fluidly from left to right when she would read, so she could not properly comprehend what she was reading. It felt like her eyes were jumping. For these eye muscle injuries, she underwent ocular therapy. She had to retrain her eyes to function together. She used a line guide to help her eyes focus on one word at a time. Everywhere she looked was blurry so Lily received glasses, something she never would have needed before her concussion. The mixture of the blurred letters along with entire words jumping around made her lightheaded and nauseous. So nauseous that she did not have an appetite for even her favorite meals.

Social

As part of Lily’s recovery, doctors recommended that she slowly re-enter school in strictly a social context to try and re-assimilate her nervous system back into bright lights and constant noise. This meant attending lunch or an after-school activity, such as a basketball game. The timing of her appearances to school was confusing to friends and classmates, as they did not understand why Lily was healthy enough to socialize, but not healthy enough to come back to class. Lily tirelessly tried to explain the difference between a typical concussion and the ever more devastating post-concussion syndrome she was experiencing. Although Lily tried to slowly re-enter school in the winter for social purposes, she was still in so much pain that she decided it was best to remain out of school to focus solely on her recovery.

Life in the low-risk lane

“People don’t understand that each person is unique and each brain is unique and recovers in a different way,” Lily’s mother explained. Most teenage girls who suffer concussions slowly continue to get better. However, there are a small percentage of girls who get worse before they get better. Even when accounting for genetic make-up, location of concussion, manner of injury, number of prior concussions, and environment, there is no simple answer as to why one person’s symptoms are drastically different from those of someone else suffering a similar concussion. Lily’s biggest issue was that her third concussion was not reported so it went untreated as she continued with her summer camp experience and vigorous exercise for months after the incident.

When January came and the spring semester began, Lily realized she was not recovered enough to attend school so she continued her medical leave until the end of junior year. This was a hard decision for her, as it meant not graduating on time with the grade she had been with since elementary school. “I’ve already had to reinvent myself so many times. What’s one more time?” Lily jokes as she prepares to enter her junior year.

Reflecting on the struggles of daily life after three concussions, Lily adds, “I now live my life in fear of getting hit. When people picture concussions, they imagine a sports injury, but concussions can happen so easily in everyday life. You have to have more body awareness. It’s frustrating because there are so many things, even outside of sports, that I don’t do because I can’t put my head at risk.”

Today, Lily is back in school and thriving. Her reading and comprehension skills are fully recovered, her balance has improved, she is returning to her former physically fit self, and she has rejoined all of the social activities with friends that she enjoys. While she could not have recovered without the support of her parents and help of numerous doctors and therapists, she also credits her patience, perseverance and resiliency, traits she learned playing sports, in enabling her to make a well-earned recovery.

You May Also Like

Living with PCS can be hard. Find out how to cope with persistent symptoms from medical experts and others who have experienced PCS.

Coping with PCS

Caring for someone with an invisible injury can be especially difficult. Learn how to best be there for your loved one with PCS.

Caregiving for PCS