Legacy Stories

Ron Lorentzen played middle and high school football in Port Angeles, Washington. He went on to become a cheerleader at the University of Washington and served as a Seabee in the Vietnam War. Around 2002, Lorentzen began to struggle with his memory and other neurological issues. He died on September 16, 2019 at 75 years old. After his death, his brain was studied at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank, where researchers diagnosed him with Stage III (of IV) Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). His first wife Sandy wrote his Legacy story to share how CTE afflicted Ron in the hope his tragedy can prevent future cases of the disease.

By Sandy Lorentzen, Ron’s first wife,

Our big question now has an answer - Ron suffered from Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), Stage III (of IV). Thanks to the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank, I also realize there was no saving him. The timebomb had been ticking for perhaps a decade before we met. Unanswerable questions remain. Could we, would we, have lived differently, knowing middle and high school football would be his undoing? Comparing Ron’s fate to most others in the Legacy Donor Gallery’s Youth and High School section, so many dying in midlife or early adulthood, and worse, in their teens, I find a new definition of lucky. At least Ron got to live out seven decades, albeit often in poor health.

Back in 1966, two quarters before college graduation, his life was upended by skipping a second ROTC reserve weekend to study for finals. He wound up in boot camp three weeks later and then the Seabees, attached to a Marine construction battalion on the Chu Lai and Phu Bai military bases in Vietnam.

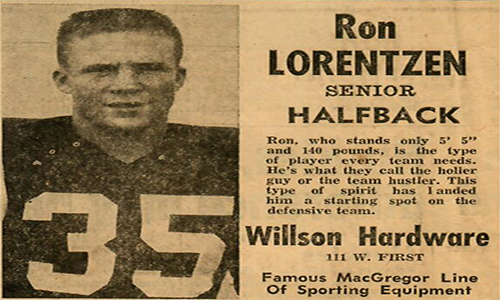

After two eight-month tours of duty, Ron returned to the classroom. We met then and married a few months later. He was funny and kind. Getting acquainted, he spoke little of Vietnam, more about his happy high school years, mostly on the football field as a defensive linebacker and offensive halfback. He was voted honorary co-captain and was admired for going all out, winning the inspirational player award twice.

Off the field, he had been involved in everything; named Boy of the Year by a civic club, junior class president, homecoming royalty, and parent student council member. Too small of stature to play college ball, he joined the University of Washington cheerleading squad and served as pledge chairman for his fraternity. He brought home two medals from the war, both awarded to him for diving competitions in the Olympics of Hue, imperial city on the Perfume River. On separate outings, I watched him save a toddler from being swept into the ocean, and a young man he noticed floundering in a river’s eddy.

With the war and college now over, everything seemed possible. Ron landed a job at a Seattle advertising agency and then segued into broadcasting, eventually becoming a producer. We discovered classical music, theater, and art galleries. He developed new talents such as drawing freehand pen and ink replicas of buildings, calligraphy, constructing furniture, and remodeling. He built a darkroom in our apartment and became a fine photographer.

Symptoms of ulcerative colitis began by age 30. In 1999 his colon was removed, and miraculously his gout disappeared too. He anticipated, at last, a life free of pain. A biopsy performed during the surgery revealed primary sclerosing cholangitis, an inflammatory condition of the liver diagnosed in children and adults. More than 75 percent of people with PSC also have colitis, and a liver transplant is the only cure. He gave no thought to this new potential death sentence. By then, we had gone our separate ways. He had become a San Francisco TV talk show producer and married the host.

They were retired, living in wine country with a summer home on the Russian River when Ron’s CTE symptoms surfaced in 2002. He awoke one morning confused, suffering from what ER notes described as “global amnesia, an episode of sudden transient memory loss and lightheadedness.” Quizzed on examination, he got the year wrong, he couldn’t remember the president’s name or recall three objects after five minutes, but he was able to correctly interpret a proverb and count backwards from 100 by sevens. A few months later, he felt lightheaded on the golf course. Seven months after that, he experienced what was diagnosed as a complex partial seizure and prescribed an anti-convulsant. From then on, Ron’s life became a maelstrom of emergency room visits for neurological symptoms that came and went, a battle with alcoholism and a dissolving marriage.

In 2011, Ron’s niece Jennifer began inquiring about his well-being. She learned divorce papers had been filed and after a third in-patient rehab, Ron was transferred to a Santa Rosa group home. Recently fired for slipping Ron liquor, a female staffer was continuing to ask him for money by phone. Unwilling to let this be his fate, we decided to go rescue him.

To sort things out, Ron moved in with Jennifer and her family in Arizona. As his health continued to decline, he needed more help, so after a few months he moved to a group home in Scottsdale. There he remained. Cloistered from life itself, he easily maintained sobriety, rarely left his bedroom, and talked to Jennifer and me by FaceTime. We spoke 20 times a day in his last two years. During our divorce so many years before, we said maybe we could be happy together again when we were old, and in a way, that’s how things turned out. It mattered not that I lived far away, had a new partner and a daughter. To us, divorce seemed a technicality when it came to the vow of in sickness and in health.

In February of 2019, the group home called to say Ron was losing weight. By July, hospice was suggested. Never one to complain, he remained his usual sunny self on FaceTime, so this alternate reality felt more like a dream. When Jennifer and I visited in August, he was subdued but seemingly comfortable. We held hands, talked about the upcoming election, about old times, and listened to our favorite music. I asked where he thought we should donate our bodies when our time was up. For him, the Boston University Brain Bank was the obvious choice since he had mentioned many football concussions. After games, Ron said he would sometimes wake up on the school bus heading home with no recollection of coming off the field.

Do people know they are about to die? If Ron did, he did not let on. Two months before, perhaps he had an inkling. One evening he said he thought we should separate. Since we lived in different states and almost never saw each other, I asked why. In the preceding months, Ron’s speech had become somewhat garbled and I would often ask him to repeat himself. He explained he thought my mind was so much deeper than his. Maybe he was having trouble following some subject I had blathered on about in a previous conversation. But he called again twenty minutes later and again said we should separate. Was it his way of letting me know we soon would? Maybe it meant nothing. His final evening over a stretch of several hours, he called 50 times and then we said good night. At 3 a.m., he went to the bathroom, returned to his room, and died in bed. I’m comforted by the idea that until his final minutes when he vomited blood, Ron may have thought it was a night like any other, and if he was in pain, he didn’t know it was his last.

His life was exuberantly and tragically lived. Knowing that his fate might now help improve the lives of others with CTE, or better still prevent the condition, would give him great satisfaction, and in that, there is solace.