Legacy Stories

Nate Woodring

This is the story of our youngest of three boys, Nate, who we tragically lost in 2016 at age 23. It’s the story of a passionate young musician beloved by his family and friends. It’s also the story of a boy who took too many hits to the head playing youth tackle football, who could not overcome his depression no matter how hard he and his family tried. We hope Nate’s story serves to help other families so they don’t have to experience what we have.

By Jennie and Bob Woodring

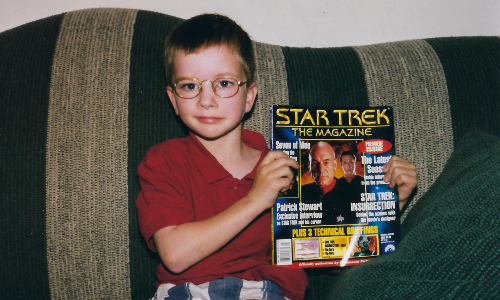

As a child, Nate was smart, happy, determined, motivated, always striving to be his best – and passionate about the things he loved. He could tell you everything about giant squids when he was five (“they have eyes the size of dinner plates”) and knew the story lines of every Star Trek Next Generation episode when he was in grade school. In fourth grade, he found his passion when he started playing drums with the school band.

Nate was a kid who never had to be told to practice. To the contrary, we had to ask him to stop playing the drums so he wouldn’t bother the neighbors, though we suspect they didn’t really mind hearing his music, especially as he got older. In high school, Nate was inspired by his band director to participate in the jazz program, which helped set the trajectory of his career path. Nate was a dedicated and talented musician, a deeply spiritual person, and an Eagle Scout. He was influenced by great jazz masters like John Coltrane to give his all with music. In his personal journal, he wrote, “I believe my music comes from a higher power.”

Nate went on to Michigan State University to major in jazz studies, and graduated in 2014. To all who knew him, Nate was a musician. He worked summers playing jazz at the Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island in Michigan for several summers, including the summer after he graduated. Shortly after, he earned a spot in a cruise ship band, and worked as a drummer in the Mediterranean for four months, coming home in March of 2015.

When Nate arrived at the airport upon returning from the cruise ship gig, the young man we welcomed home at the airport was not the Nate we knew. It was a testament to his internal will that he had even been able to navigate the trip home. He was nearly catatonic, had difficulty speaking or answering questions, and could barely eat or function. At the ER the next morning he was diagnosed with major depression with psychosis and spent ten days as an in-patient in psychiatric care.

Nate came home after his hospital stay, and during the following fourteen months, he and we did everything we could to help him with the tools we had. Bob changed the way he did his job and mostly stayed at home, to be with Nate and help in any way possible. While we were shocked and blindsided when Nate came home from the ship, in retrospect, we realize that his mental decline had begun earlier, as evidenced by what we thought was seasonal affective disorder each fall at college. His symptoms always appeared to go away shortly after onset, and didn’t seem cause for great concern.

For those diagnosed with depression, there are many methods for improving one’s state of mind including exercise, medications, and therapy. Nate doggedly tried them all, but nothing seemed to help. He was plagued by intense anxiety, memory loss, and what we realize now were symptoms of dementia. Along the way he became suicidal, and we eventually realized we couldn’t keep him safe at home. Three weeks before he died, Nate moved to a therapeutic farming community – a move we all felt was the best solution, given what we knew at the time. We still believe a therapeutic community is the right answer for many young people suffering from mental illness – but Nate never got better. Early on May 20, 2016, before sunrise, he ran out into a two-lane state route and was killed by an oncoming pickup truck.

As Nate’s parents, we did the things you do when you lose a child. We told his brothers, his sister-in-law, his grandparents and the rest of the family that he had taken his own life. We wrote an obituary, planned a funeral, began grieving, and tried to adjust to the new reality thrust upon us.

For Bob especially, the lack of explanation of a cause of Nate’s illness was a nagging presence, and he had accepted the reality that he might never have any answers. There was no history of mental illness in our families, and Nate’s severe symptoms were dramatic and unresponsive to treatment. There were three different diagnoses for his condition, every conceivable medication was tried, and nothing helped. There were many questions and no answers, either while he was alive or after.

We know now, three years later, that there is much more to Nate’s story.

Ever the sports fan, Bob read a Sports Illustrated article about Tyler Hilinski, the Washington State quarterback. It was difficult to get through the article because Bob knew the ending. Tyler had taken a hit in a game that changed his actions and personality, eventually ending in suicide. His parents had his brain analyzed and found that he had CTE. At that moment, Bob thought about Nate playing youth football from ages 11 through 14. Even though it seemed so long ago, Bob felt there could be a connection given the way Nate approached football, and everything else in life.

Bob immediately started a web search and found an article on the Concussion Legacy Foundation website about CTE. In that article he saw that repeated hits to the head before the age of 12 may make the brain less resilient to disease. The article also described symptoms of CTE, which include depression and problems with thinking. At that moment Bob realized that CTE symptoms may have been what Nate had been experiencing toward the end of his life. All of a sudden, we went from no answers to possibly every answer about Nate. In the proceeding days, Bob spoke with several medical professionals that all completely agreed with his conclusions.

Nate was one of the smaller kids on the team but he played with a lot of heart and determination. In 2004, at age 12 and in 7th grade, Nate received a trophy as the most improved player on the team. The coaches loved his intensity and the way he took on anyone, regardless of how big they were. He played linebacker and fullback on a primarily running team, which meant he was hitting someone on most every play.

Most Evanston Junior Wildkit Football players end up going on to play for Evanston Township High School. Nate played through his freshman year, age 14. He also played in the marching band which was an extension of his real passion: music. At the beginning of sophomore year, Nate had to choose between football and marching band and he chose the path of music – despite pleas from his coach to stay with football.

Nate excelled at his craft as one of the best drummers in the area. He became a great musician and jazz aficionado. Nate has inspired us to develop a love of jazz. We are proud of the way Nate approached life and are grateful to have found some sense out of a senseless situation.

We will never know for sure if Nate had CTE. We can’t be certain because his brain was not studied after death. But we suspect it based on Nate’s symptoms and other, similar cases. Former youth athletes have been diagnosed with CTE after death following exposure to head trauma at young ages. Athletes like Joseph Chernach, who was found to have Stage II CTE at age 25, and Kyle Raarup, who was found with Stage I CTE at age 20, are examples to consider alongside Tyler Hilinski.

As Nate’s parents, we bore witness to his struggle and we’re convinced that exposure to brain trauma at a young age, and subsequent CTE, caused his symptoms. Our conviction drives us to fight so that more people know the risks associated with exposure to brain trauma.

We hope to leave a legacy of helping others and we believe, for now, the best approach will be to attempt to convince parents that there is no reason to let their children play tackle football before the age of 14. The fact of the matter is kids don’t receive college scholarships in middle school, and exposing them to brain trauma at such a young age is not worth the risk. Given the popularity of football in this country it will not be easy, but we are up for the challenge. We did not have the knowledge of the consequences back in 2003, and we are ready to tell everyone Nate’s story. Our approach is simple. What do you love more – football or your child?

Suicide is preventable and help is available. If you are concerned that someone in your life may be suicidal, the five #BeThe1To steps are simple actions anyone can take to help someone in crisis. If you are struggling to cope and would like some emotional support, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 to connect with a trained counselor. It’s free, confidential, and available to everyone in the United States. You do not have to be suicidal to call.

Are you or someone you know struggling with lingering concussion symptoms? We support patients and families through the CLF HelpLine, providing personalized help to those struggling with the outcomes of brain injury. Submit your request today and a dedicated member of the Concussion Legacy Foundation team will be happy to assist you. Click here to support the CLF HelpLine.

Suicide Prevention Resources

Nobody should have to go through a crisis alone. Dial 9-8-8 if you or a loved one is in crisis or suicidal.

Suicide Prevention Lifeline

We can all play a role in preventing suicide. Learn the five steps to help you #BeThe1To support someone in crisis.

#BeThe1To Resources