Legacy Stories

Read this excerpt from Spartan Verses by Pat Gallinagh; edited by Jim Proebstle, author of Unintended Impact.

Pat and Jim were teammates of Bubba's at Michigan State University during the 1965 and 1966 seasons, when they won back-to-back National Championships.

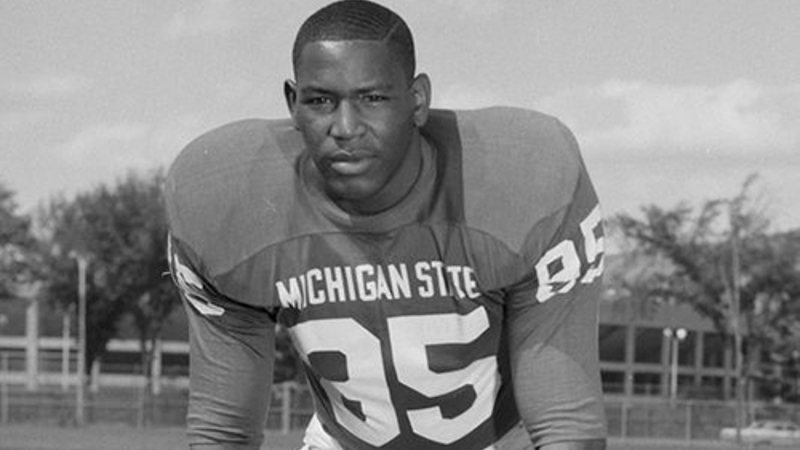

Every now and then you run into a character who is “bigger than life.” Charles “Bubba” Smith of Beaumont, Texas at 6 ft. 7 in. and 270 lbs. did both literally and figuratively fit that mold. Bubba was a passenger on the “underground railroad” of talented black athletes from the Jim Crow south that prohibited players from playing in the South. He, along with many others, was actively recruited by Coach Duffy Daugherty of Michigan State University in the sixties in what was to become one of Duffy’s hallmark achievements. Given a choice, Bubba probably would have preferred playing at a major university in his home state, like the University of Texas or Texas A&M.

By far the biggest member of the Spartan freshman football team in 1963, it was impossible for him to blend in with the thousands of new students pouring into East Lansing from all over the world. He stood out like a giant oak in an apple orchard. Many students stared at him in disbelief and rather than shy away from the fact that he was a behemoth, Bubba played the role to the hilt using his comedic talent to pretend to be a dim-witted, bumbling, good-natured oaf. A skill he would parlay into a successful acting career in Hollywood. He was a teaser and practical joker pushing his teammates’ buttons and his coaches to their limits with his pranks. In reality, Bubba was a good friend to those around him and never actively sought out the notoriety that just naturally presented itself.

There were some members of the college community who thought football players were modern day Neanderthals who dragged their knuckles on the ground as they prowled the campus. Others felt the football scholarships were a form of color-blind affirmative action for the intellectually challenged. Bubba was neither uncivilized nor stupid, although his persona did often catch the attention of the administration and coaching staff as his celebrity peaked during his senior year. The many Bubba sighting and urban legend stories that still exist to this day on the MSU campus are telltale of a man who easily adapted to the “big stage.”

With his enormous physical talent, he was often accused of not using it to the fullest on the field. There may have been some truth to that at times, but if so, it probably had more to do with peer pressure than not making an effort. When you are the biggest kid in your class you are often chided for using your superior strength and size by your classmates. Being labeled a class bully was not a coveted title back then or now, so unless prodded to do so by teammates or coaches, he sometimes may have appeared that he wasn’t trying very hard. And, it may have been because he didn’t have to. We should ask Terry Hanratty, Notre Dame’s QB who was permanently knocked out of the 10-10 Game of the Century, what he thought after a crushing tackle by Bubba in 1966. In any event, most teams ran their offense away from him as the fans in the stands chanted, “Kill, Bubba, Kill.” In the locker room Bubba was a very unique actor and just one of the guys adding tremendous chemistry and humor to a determined team of athletes.

The pros knew what they were doing when he was selected as the number one draft pick in 1967. He helped lead Baltimore to two Super Bowl performances in his five years with the Colts, winning Super Bowl V in 1971. After the Colts he spent two seasons each with Oakland and Houston. As one of the best pass rushers in the game, Bubba often drew two blockers, yet was effective enough to make two Pro Bowls, one All-Pro team and be recognized through the Vince Lombardi Trophy. Bubba Smith was enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame in 1988. The Big Ten Defensive Lineman of the Year Award bears his name. It is not documented to what extent he experienced concussions during his playing years. Clearly, there was significant punishment. What is known, however, is that the Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) discovered in Bubba’s brain by neuropathologists at Boston University Medical Center was classified as Stage III CTE with symptoms that included cognitive impairment and problems with judgment and planning. Bubba died on August 3, 2011 at the age of 66. Smith was the 90th former NFL player found to have had CTE by the researchers at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank out of their first 94 former pro players examined.

He was likely on his way to the NFL Hall of Fame until landing on a sideline marker in an exhibition game that curtailed his playing career and headed him into his acting career. Between 1979 and 2010, Bubba appeared in various roles in over twenty-two movies and television performances. Probably his most noteworthy efforts came in his role of Moses Hightower in the Police Academy movies and his role with Dick Butkus in the “taste great…less filling” Miller Lite commercials. It was this beer commercial contract that lead to his proudest moment. When he realized that he was being used as an instrument to promote drunkenness; he walked away from his contract. His matured social consciousness took both strength and courage to break such a lucrative deal. He valued integrity over money. In the final analysis he was just Bubba: friendly, easy to approach, generous and never getting “too big” as a result of his success.

Bubba Smith is survived by his son, Nathan Hatton.